Even though I was sure that I'd like it, I've been avoiding watching this film, because I knew that its premise - boy and girl meet, feel a connection, spend a night together talking about life and love, fall at least a little bit in love with one another, then part - was almost guaranteed to be ruinous for my state of mind, particularly in a susceptible mood. So tonight, feeling not particularly susceptible and rather in the mood to be inspired, I sat down with Before Sunrise at last, to find that it is indeed lovely, bittersweet, and, in fact, ultimately far more cheering than crushing.

So many little perfect moments - the initial awkwardness of the first conversation in the lounge car, the mutual pull and restraint in the record store listening booth, the poignant conversation in which it's decided that they'll only spend the one night together...but the magic moment for me comes when Celine is talking about how, if we're ever to find this thing that we're all looking for, it must be in the space between people, spinning my thoughts about shared imaginative spaces and understanding others in a way which I hadn't expressed before, but which made perfect sense as soon as I heard it: "if there's any kind of magic in this world, it must be in the attempt of understanding someone, sharing something ... I know, it's almost impossible to succeed ... but who cares, really ... the answer must be in the attempt".

It's a fantasy - an idealisation - a romanticisation - a romance - but it all rings so true... which is all the more bittersweet, of course, for while the film is utterly truthful and note-perfect in its rendition of the characters of, and interactions between, Jesse and Celine (they both seem like people whom one might meet at any time, anywhere, and the ways in which they relate to each other are equally genuine and natural-seeming, perfectly observed; the film could've gone wrong at so many points, but somehow it never does), encounters such as theirs in real life are all too rare...I guess that the only thing to do is to keep on looking.

Sunday, December 11, 2005

Saturday, December 10, 2005

British Art & the 60s from Tate Britain @ NGV International

Had a free afternoon in the city, so thought that I'd check this out; arrived at 3ish, and two hours (gallery closes at 5) proved to be almost exactly the right amount of time to put aside for it.[*] Given that its connecting thread is a historical period and place rather than being, say, thematic or movement-based, it's unsurprising that the exhibition should be a bit of a mish-mash, covering quite a lot of ground.

There's a fair bit of abstract stuff, some 'optical paintings' (such as those of Bridget Riley [left], which I particularly liked), a lot of pop-art (colourful and sometimes - though not always - kitsch) and related streams, sculptures, recreations of installations, photographs (Vietnam War, Beatles, Jean Shrimpton (gosh she was a beauty), Mick Jagger, Rudolph Nureyev, and other such iconic figures), a jukebox room in which a Wurlitzer played 60s hits (for some reason, "Delilah" kept coming up), and quite a bit of archival material (videos, written documentation, etc - my favourite of these is the fabulously weird footage of Yoko Ono doing a 'performance' in which she sat on stage, deadpan, as members of the audience took it in turn to come up and cut bits of her dress off).

There's a fair bit of abstract stuff, some 'optical paintings' (such as those of Bridget Riley [left], which I particularly liked), a lot of pop-art (colourful and sometimes - though not always - kitsch) and related streams, sculptures, recreations of installations, photographs (Vietnam War, Beatles, Jean Shrimpton (gosh she was a beauty), Mick Jagger, Rudolph Nureyev, and other such iconic figures), a jukebox room in which a Wurlitzer played 60s hits (for some reason, "Delilah" kept coming up), and quite a bit of archival material (videos, written documentation, etc - my favourite of these is the fabulously weird footage of Yoko Ono doing a 'performance' in which she sat on stage, deadpan, as members of the audience took it in turn to come up and cut bits of her dress off).

A few which particularly stood out (I took notes!), apart from those which I've already mentioned:

A few which particularly stood out (I took notes!), apart from those which I've already mentioned:

* Robyn Denny - "Golem 1 (Rout of San Romano)". Very striking, brightly coloured, large (in fact many of these works are particularly large). Bits of corrugated cardboard and various collaging effects happening, painted over in vivid colours. In some odd way, reminded me of Picasso's "Guernica" - the same kind of riot of overlapping curves and angles, and I think the composition may've been somewhat similar, too.

* Richard Hamilton - "Interior II". Neat collage-type thing, combined with actual painting.

* Michael Andrews - "All Night Long". More of a traditional oil painting, depicting a decadent-looking party, sophisticates, artistes and beautiful people living it up while looking vaguely haunted. Appealed to me muchly.

* Allen Jones - "Man Woman" [above]. Colourful, playful and oddly sensuous.

* Phillip King - "Tra, La, La". Plastic sculpture in eggshell blue and pale pink, probably about 10 feet high, three segments topped by a twisty sort of thing. Not sure why I liked it so - may've just been the colours.

A fun collection - moving through the rooms feels like an exploration because of the diversity of types of works, and all the colours, textures and three-dimensionality keep things interesting (I dug the recreation of David Medalla's bubble sculpture, "Cloud Canyons"!). Neat!

* * *

[*] Though some time was spent talking with a (presumably bored) security guard about art and life, putting paid to my theory that they only come up and start talking to pretty girls (because, y'know, invariably my visits to the NGV are either en seul or with some pretty girl or other on my arm...).

There's a fair bit of abstract stuff, some 'optical paintings' (such as those of Bridget Riley [left], which I particularly liked), a lot of pop-art (colourful and sometimes - though not always - kitsch) and related streams, sculptures, recreations of installations, photographs (Vietnam War, Beatles, Jean Shrimpton (gosh she was a beauty), Mick Jagger, Rudolph Nureyev, and other such iconic figures), a jukebox room in which a Wurlitzer played 60s hits (for some reason, "Delilah" kept coming up), and quite a bit of archival material (videos, written documentation, etc - my favourite of these is the fabulously weird footage of Yoko Ono doing a 'performance' in which she sat on stage, deadpan, as members of the audience took it in turn to come up and cut bits of her dress off).

There's a fair bit of abstract stuff, some 'optical paintings' (such as those of Bridget Riley [left], which I particularly liked), a lot of pop-art (colourful and sometimes - though not always - kitsch) and related streams, sculptures, recreations of installations, photographs (Vietnam War, Beatles, Jean Shrimpton (gosh she was a beauty), Mick Jagger, Rudolph Nureyev, and other such iconic figures), a jukebox room in which a Wurlitzer played 60s hits (for some reason, "Delilah" kept coming up), and quite a bit of archival material (videos, written documentation, etc - my favourite of these is the fabulously weird footage of Yoko Ono doing a 'performance' in which she sat on stage, deadpan, as members of the audience took it in turn to come up and cut bits of her dress off). A few which particularly stood out (I took notes!), apart from those which I've already mentioned:

A few which particularly stood out (I took notes!), apart from those which I've already mentioned:* Robyn Denny - "Golem 1 (Rout of San Romano)". Very striking, brightly coloured, large (in fact many of these works are particularly large). Bits of corrugated cardboard and various collaging effects happening, painted over in vivid colours. In some odd way, reminded me of Picasso's "Guernica" - the same kind of riot of overlapping curves and angles, and I think the composition may've been somewhat similar, too.

* Richard Hamilton - "Interior II". Neat collage-type thing, combined with actual painting.

* Michael Andrews - "All Night Long". More of a traditional oil painting, depicting a decadent-looking party, sophisticates, artistes and beautiful people living it up while looking vaguely haunted. Appealed to me muchly.

* Allen Jones - "Man Woman" [above]. Colourful, playful and oddly sensuous.

* Phillip King - "Tra, La, La". Plastic sculpture in eggshell blue and pale pink, probably about 10 feet high, three segments topped by a twisty sort of thing. Not sure why I liked it so - may've just been the colours.

A fun collection - moving through the rooms feels like an exploration because of the diversity of types of works, and all the colours, textures and three-dimensionality keep things interesting (I dug the recreation of David Medalla's bubble sculpture, "Cloud Canyons"!). Neat!

* * *

[*] Though some time was spent talking with a (presumably bored) security guard about art and life, putting paid to my theory that they only come up and start talking to pretty girls (because, y'know, invariably my visits to the NGV are either en seul or with some pretty girl or other on my arm...).

Thursday, December 08, 2005

Alison Lurie - Foreign Affairs

This one won a Pulitzer, which is kind of interesting given that its America - and American characters - are seen primarily in connexion with England and their dealings with the mother country. Anyway, like Love & Friendship, it's an absolute breeze and a delight to read. In terms of characters, Foreign Affairs is basically a two-hander - there's Vinnie Miner, an Anglophile professor in children's playground rhymes, 50ish, plain, and dogged (literally) by an imagined demon familiar who represents self-pity, embodied in the form of a dog (which, incidentally, makes a heck of an opening line for the novel: 'On a cold blowy February day a woman is boarding the ten a.m. flight to London, followed by an invisible dog'), and Fred Turner, a youngish PhD specialising in the poetry of 18th century author John Gay and who, in stark contrast to Professor Miner, is blessed with movie star good looks. Colleagues but only slightly acquainted at a NY university, their paths cross when their work brings each to London.

What follows is a sharp, keenly observed kind of modern comedy of academic manners, intersecting with tv stars, publishing types, business magnates, social hostesses and general gads about town, in a round of drinks parties, weekends away, and fabulous lunches. Characters are thrown into deepest dudgeon by unfavourable reviews of their work, frustrated half to death by working conditions at public libraries, dwell incessantly on their relations with one another, continually condescend to those who they consider beneath them in the most well-mannered way possible, &c.

Then, too, there's what one reviewer (on the book's back cover) refers to as the novel's 'merciful vision', which is a great way of characterising the sympathy with which Lurie renders her characters and their movements...I could never develop a 'reader's crush' on any of them, but I do often feel the urge to give them a big hug and some (sure to be disregarded) advice. Some of the minor characters aren't as well developed as they could be, but perhaps that comes somewhat with the territory, and at least one never feels that they're mere archetypes or mouthpieces for particular points of view. Henry James is a good reference point (suitably updated, of course, and perhaps somewhat less intricately drawn - though this, too, may be appropriate to the times); indeed, Lurie explicitly refers to James at a couple of points in Foreign Affairs.

Of all the stuff that I've read this holiday so far (and it's been a pretty voracious period), Lurie's are the books which have been the most purely pleasurable, I reckon.

What follows is a sharp, keenly observed kind of modern comedy of academic manners, intersecting with tv stars, publishing types, business magnates, social hostesses and general gads about town, in a round of drinks parties, weekends away, and fabulous lunches. Characters are thrown into deepest dudgeon by unfavourable reviews of their work, frustrated half to death by working conditions at public libraries, dwell incessantly on their relations with one another, continually condescend to those who they consider beneath them in the most well-mannered way possible, &c.

Then, too, there's what one reviewer (on the book's back cover) refers to as the novel's 'merciful vision', which is a great way of characterising the sympathy with which Lurie renders her characters and their movements...I could never develop a 'reader's crush' on any of them, but I do often feel the urge to give them a big hug and some (sure to be disregarded) advice. Some of the minor characters aren't as well developed as they could be, but perhaps that comes somewhat with the territory, and at least one never feels that they're mere archetypes or mouthpieces for particular points of view. Henry James is a good reference point (suitably updated, of course, and perhaps somewhat less intricately drawn - though this, too, may be appropriate to the times); indeed, Lurie explicitly refers to James at a couple of points in Foreign Affairs.

Of all the stuff that I've read this holiday so far (and it's been a pretty voracious period), Lurie's are the books which have been the most purely pleasurable, I reckon.

Wired to the world

It's not unusual for an everyday sound to trigger a sort of musical recollection on my part, whereby the sound causes some more or less familiar record, a part of which it resembles, to begin playing in my head, usually only for a few seconds; sudden bangs of the right kind often trigger the first few bars of "Like A Rolling Stone", for example. Sometimes, one of those everyday sounds has a slightly different effect - it puts a new melody in my head, which would be damn useful if I were a songwriter and is still a source of minor happiness even given that I'm not.

So anyway, I had a visitation of the former kind this afternoon - the sound could've come from anywhere, the song was "Rebellion (Lies)" - and it got me briefly thinking about this whole 'music in the air' thing. Too lazy to unravel all of those threads and reconstruct them here, but I then jumped to the way in which I tend to have portable music with me (ie, a discman; one of these days, I'll upgrade to an mp3 player, though probably not during these money-conscious hols) wherever I go (when out of the house, at any rate).

I've wondered before what effect the constant plugged in-ness has on my experience of the world - there was a period when I often got little electric shocks delivered directly from the buds to my ears (Not Fun, needless to say - I never did get to the bottom of that, but I think it had something to do with the shoes I had at the time), which, on days when I was feeling sensitive, prompted me to sometimes go about my business sans discman, and I remember noticing how much freer and more connected to the wider world I felt at those times, neither of which was anything much of a surprise, although their pronouncedness was a bit unexpected. For any number of reasons, anyway, I suspect that there'll be less and less earphone/headphone listening while out and about in the future, at least once this summer break ends.

So anyway, I had a visitation of the former kind this afternoon - the sound could've come from anywhere, the song was "Rebellion (Lies)" - and it got me briefly thinking about this whole 'music in the air' thing. Too lazy to unravel all of those threads and reconstruct them here, but I then jumped to the way in which I tend to have portable music with me (ie, a discman; one of these days, I'll upgrade to an mp3 player, though probably not during these money-conscious hols) wherever I go (when out of the house, at any rate).

I've wondered before what effect the constant plugged in-ness has on my experience of the world - there was a period when I often got little electric shocks delivered directly from the buds to my ears (Not Fun, needless to say - I never did get to the bottom of that, but I think it had something to do with the shoes I had at the time), which, on days when I was feeling sensitive, prompted me to sometimes go about my business sans discman, and I remember noticing how much freer and more connected to the wider world I felt at those times, neither of which was anything much of a surprise, although their pronouncedness was a bit unexpected. For any number of reasons, anyway, I suspect that there'll be less and less earphone/headphone listening while out and about in the future, at least once this summer break ends.

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

China Miéville - Looking For Jake

A collection of shortish stories and other pieces of imaginative fiction, many previously published (two I'd read before - Miéville's entry in the Lambshead compendium, and a creepy little number called "Details" which apparently appeared in some kind of Lovecraft tribute a few years back...). As is often the case with such collections, some of the author's preoccupations and recurring themes come through a bit more clearly than in his/her longer-form writings - here, it's Miéville's socialist politics and his fascination with place and space which are particularly prominent (both are plenty legible in his novels, too, but can sometimes get lost amidst the crazy architectures of those longer works). Also evident is his facility with the unexpected twist or shift in perspective - never done in a way which comes near gimmickry, and always forcing the reader to re-evaluate all that has come before. And I'm not sure if I've noticed the compactness of Miéville's prose before - its lean expressiveness - which was, I suppose, easily lost in the baroque multiplication of detail which characterises his writing.

"The Tain" is the longest of these tales, though probably not the most substantial. Taking a Borges fragment as its jumping-off point, it's a neat take on the vampire mythos, with particular emphasis on the significance of mirrors (and who doesn't like a good post-apocalyptic London tale?). In a somewhat similar vein is the title story, recounting events in a London which has been destroyed - or overtaken - by entropy. "Jack" recounts the story of Jack Half-a-Prayer, from the New Crobuzon books, going some way to explaining his significance and capturing the darkness at the heart of the series, and also getting me thinking more about the connection between the Remade and marxist ideas of human labour and commodification.

There's a pervasive air of ruinedness, decay and unease to nearly all of the stories, showing that Miéville's knack for creating such atmospheres isn't limited to the steam-punk sprawls of his novels (King Rat excepted, I guess), and of course they tend to be pretty dark. "'Tis The Season" is a nice exception - wearing its anti-capitalist principles on its sleeve, it considers the (initially trite-seeming) scenario of all of the apparatus of Christmas (holly, carol-singing, coloured paper as giftwrap, etc) having been patented and corporatised, and then runs with it in delightful style, savaging capitalism while also affectionately ridiculing a lot of the tendencies and splinters of the contemporary left activist scene, even managing a wonderfully bathetic ending.

As always with Miéville's writing, sailed through this in no time at all.

"The Tain" is the longest of these tales, though probably not the most substantial. Taking a Borges fragment as its jumping-off point, it's a neat take on the vampire mythos, with particular emphasis on the significance of mirrors (and who doesn't like a good post-apocalyptic London tale?). In a somewhat similar vein is the title story, recounting events in a London which has been destroyed - or overtaken - by entropy. "Jack" recounts the story of Jack Half-a-Prayer, from the New Crobuzon books, going some way to explaining his significance and capturing the darkness at the heart of the series, and also getting me thinking more about the connection between the Remade and marxist ideas of human labour and commodification.

There's a pervasive air of ruinedness, decay and unease to nearly all of the stories, showing that Miéville's knack for creating such atmospheres isn't limited to the steam-punk sprawls of his novels (King Rat excepted, I guess), and of course they tend to be pretty dark. "'Tis The Season" is a nice exception - wearing its anti-capitalist principles on its sleeve, it considers the (initially trite-seeming) scenario of all of the apparatus of Christmas (holly, carol-singing, coloured paper as giftwrap, etc) having been patented and corporatised, and then runs with it in delightful style, savaging capitalism while also affectionately ridiculing a lot of the tendencies and splinters of the contemporary left activist scene, even managing a wonderfully bathetic ending.

As always with Miéville's writing, sailed through this in no time at all.

Kathleen Edwards - Failer

The one that came before Back To Me, and her debut, I think. More or less the same kind of stuff - melodic singer-songwriter sweetness mingled with country rasp and twang, and done pretty well. A bit less expansive than Back To Me, and with rootsier (ie, less glossy and full-feeling) production - neither of which is a criticism, natch. Edwards' dusty voice - one of the more distinctive aspects of her music - is in fine form, though here she's more likely to be edging closer to murmuring or declaiming her vocals than, as on Back To Me, really singing them. The melodies are less immediate, though, and also, I think, maybe a bit less strong. Still, all in all, a good album.

Sunday, December 04, 2005

Gérard de Nerval - Aurélia

Some books demand to be read in particular settings, and once I'd gotten a couple of pages into Aurélia, I realised that it was one such; in particular, I reckoned, it needed to be read while on my own, at night, preferably while in a bit of a mood, and in one sitting if at all possible.

So I put it aside at the time, but earlier tonight, having decided against going out, I was lying around in my bedroom with Loveless playing softly in the background and feeling broody in an inchoate sort of way, when my eye fell on the book and I thought the time was ripe to return to it.

The blurry boundary between dreams and waking life, and the commingling of the two, has preoccupied me in the past: in an abstract, vaguely philosophical sense (phenomenology again - for what is the world, and reality, if not simply that which is present to us through experience, and are dreams not experiences just as much as those we undergo in waking life?); in recollection (sometimes, I can't work out whether something which I recall experiencing occurred 'only' in a dream or 'actually', while I was awake); and even, on occasion, quite immediately (as in the strange befuddled in-between state where I'm unsure whether I'm dreaming or awake - an uncertainty which is never entirely resolved, for there's never a clear line to be crossed between the two). In Aurélia, this blurriness is evoked - and invoked - with a fervid immediacy and incontrovertability, in which everything is drenched with a sort of heaviness, a suffocating mustiness and lushness which is the particular province of dreams, and this is generated by the dense, luxuriant prose as much as by the intersheavings of dreams with waking experiences. (Reminded me a bit of the Gormenghast books, though it's considerably more deranged than those, where ritual and stasis are all.)

It's a book which, I think, requires its reader to submit to it, and I suppose that that's what I've done by spending the last few hours wrapped up in its embrace - an embrace which is somehow both languid-drowsy and violent-turbulent. The text is a maelstrom of competing visions and ideas, heavily infused with 19th C mysticism and fascination with the Orient, along with some distinctly mystical takes on Christianity, and centred around the narrator's (Nerval's?) obsessive love for the titular Aurélia and the many forms that this (and so she) takes...I've glossed over the importance of love here and would say more about it were my thoughts on this book not such a mess (which fits the book itself!). It's compelling in its ill-formedness, coming on like the ramblings of an unhinged mind - indeed, it's framed by authorial protestations regarding the 'illness' that gave rise to the experiences it recounts - and convincing, too, possessing a perverse internal logic of its own. Not the kind of book that I'd have been likely to stumble across on my own (I came to it because Sarah had named it as one of her canonical books) but it's definitely left an impression.

Actually, this particular volume (translated and, I think, selected by one Richard Aldington), contains a few other pieces (and extracts from larger pieces) by Nerval - I'll probably read them at some point, but I wanted to set down my initial impressions of Aurélia immediately...

So I put it aside at the time, but earlier tonight, having decided against going out, I was lying around in my bedroom with Loveless playing softly in the background and feeling broody in an inchoate sort of way, when my eye fell on the book and I thought the time was ripe to return to it.

Our dreams are a second life. Not without a shudder do I pass through the gates of ivory or horn which separate us from the invisible world. The first moments of sleep are an image of death -- our thoughts are held in a cloudy swoon, and we cannot tell the exact instant when the "Ego" continues the labour of existence in another form. A vague underground chamber little by little grows lighter; the pale, gravely motionless shapes which inhabit the dwelling-place of shades emerge from the shadow and from night. The picture takes form, new light falls on these strange apparitions and gives them movement. The world of the Spirits opens before us.

The blurry boundary between dreams and waking life, and the commingling of the two, has preoccupied me in the past: in an abstract, vaguely philosophical sense (phenomenology again - for what is the world, and reality, if not simply that which is present to us through experience, and are dreams not experiences just as much as those we undergo in waking life?); in recollection (sometimes, I can't work out whether something which I recall experiencing occurred 'only' in a dream or 'actually', while I was awake); and even, on occasion, quite immediately (as in the strange befuddled in-between state where I'm unsure whether I'm dreaming or awake - an uncertainty which is never entirely resolved, for there's never a clear line to be crossed between the two). In Aurélia, this blurriness is evoked - and invoked - with a fervid immediacy and incontrovertability, in which everything is drenched with a sort of heaviness, a suffocating mustiness and lushness which is the particular province of dreams, and this is generated by the dense, luxuriant prose as much as by the intersheavings of dreams with waking experiences. (Reminded me a bit of the Gormenghast books, though it's considerably more deranged than those, where ritual and stasis are all.)

However this may be, I think that the human imagination has invented nothing which is not true, either in this world or others; and I could not doubt what I had seen so distinctly.

It's a book which, I think, requires its reader to submit to it, and I suppose that that's what I've done by spending the last few hours wrapped up in its embrace - an embrace which is somehow both languid-drowsy and violent-turbulent. The text is a maelstrom of competing visions and ideas, heavily infused with 19th C mysticism and fascination with the Orient, along with some distinctly mystical takes on Christianity, and centred around the narrator's (Nerval's?) obsessive love for the titular Aurélia and the many forms that this (and so she) takes...I've glossed over the importance of love here and would say more about it were my thoughts on this book not such a mess (which fits the book itself!). It's compelling in its ill-formedness, coming on like the ramblings of an unhinged mind - indeed, it's framed by authorial protestations regarding the 'illness' that gave rise to the experiences it recounts - and convincing, too, possessing a perverse internal logic of its own. Not the kind of book that I'd have been likely to stumble across on my own (I came to it because Sarah had named it as one of her canonical books) but it's definitely left an impression.

Actually, this particular volume (translated and, I think, selected by one Richard Aldington), contains a few other pieces (and extracts from larger pieces) by Nerval - I'll probably read them at some point, but I wanted to set down my initial impressions of Aurélia immediately...

Saturday, December 03, 2005

J. Jacques - "Questionable Content"

The world of webcomics is more or less a closed book to me, not as a matter of principle or snobbery, but simply because I've never had any particular interest in the field (I don't spend much time reading comics, and nor do I generally spend much time reading stuff on the web). That notwithstanding, though, last night I came across "Questionable Content" and ended up sitting up late to read it all the way through from the first strip through to the latest instalment (they go up on a daily basis).

Wherein lies the appeal? Well, a lot of it comes from the indie-kid characters, sarcastic, self-aware, impeccably hip, basically nice, definitively messed-up, who spend their lives talking about Sonic Youth, Pavement, Bright Eyes, Wilco, the Arcade Fire, etc, referencing websites like pitchfork and tinymixtapes, hating on emo, being ironic about the labels they wear (or don't wear), deconstructing what it is to be 'indie' and being all ambivalent about it and stuff, and engaging in other such quintessential activities...that's when they're not flirting with each other, getting drunk at bars and at each other's apartments, hanging around at the coffee shop where several of them work, talking random rubbish, and drowning in various slow-burn complicated varieties of sexual frustration born of their collective Issues. Central character Marten, a shy, skinny indie boy, sums it all up at one point when he self-deprecatingly refers to his habit of surrounding himself with sexy, intelligent girls with whom he has no chance as the 'indie-rock nerd's dream', or words to that effect.[*] (Ouch.)

Not to mention Pintsize, the cute AnthroPC who doubles as Marten's pet and sidekick, and also provides much of the humour.

So anyway, it's cute and slightly off the wall, and sometimes quite funny; the main appeal lies in the writing, but the art is colourful and engaging, too. Worth reading just because it so perfectly captures its subject - in which case, how could it fail to be entertaining and oddly truthful?

* * *

[*] Although of course he does have a chance, which is kind of the rub.

Wherein lies the appeal? Well, a lot of it comes from the indie-kid characters, sarcastic, self-aware, impeccably hip, basically nice, definitively messed-up, who spend their lives talking about Sonic Youth, Pavement, Bright Eyes, Wilco, the Arcade Fire, etc, referencing websites like pitchfork and tinymixtapes, hating on emo, being ironic about the labels they wear (or don't wear), deconstructing what it is to be 'indie' and being all ambivalent about it and stuff, and engaging in other such quintessential activities...that's when they're not flirting with each other, getting drunk at bars and at each other's apartments, hanging around at the coffee shop where several of them work, talking random rubbish, and drowning in various slow-burn complicated varieties of sexual frustration born of their collective Issues. Central character Marten, a shy, skinny indie boy, sums it all up at one point when he self-deprecatingly refers to his habit of surrounding himself with sexy, intelligent girls with whom he has no chance as the 'indie-rock nerd's dream', or words to that effect.[*] (Ouch.)

Not to mention Pintsize, the cute AnthroPC who doubles as Marten's pet and sidekick, and also provides much of the humour.

So anyway, it's cute and slightly off the wall, and sometimes quite funny; the main appeal lies in the writing, but the art is colourful and engaging, too. Worth reading just because it so perfectly captures its subject - in which case, how could it fail to be entertaining and oddly truthful?

* * *

[*] Although of course he does have a chance, which is kind of the rub.

Another writeup: Gersey - Hope Springs

The past few days, it's been all about reading and writing for me, both by choice and because my going-out style has been slightly cramped by the 'no work' (and hence, no income) rule which I've decided on for this summer. So, another piece for epinions:

"Widescreen, introspective, wistful and sometimes incandescent guitar-rock".

"Widescreen, introspective, wistful and sometimes incandescent guitar-rock".

Thursday, December 01, 2005

Michael Cunningham - The Hours

So I could hardly help reading this book in light of the film, particularly given that it was the film which inspired the reading, and particularly particularly because, it turns out, the film follows the structure of the book very closely, almost as a scene-for-scene adaptation. Well-nigh impossible to imagine how I would've responded to Cunningham's novel had I read it before coming across the film, but I have to assume that I would've liked it. As it is, I definitely liked it, but always found myself mentally leaping ahead to anticipate what I knew was coming...

In terms of the film, then:

- Overall, the film has a somewhat more dramatic bent, directed, I think, at heightening the audience's responses to Virginia, Clarissa and Laura. The first of the scenes in which Clarissa and Richard confront each other in the latter's squalid apartment, for example, has an edge and a sense of simmering anger, disappointment, almost spite, which is absent from the book's treatment, which is more polite and subdued. In another example, Clarissa's breakdown in the kitchen doesn't occur in the book - instead, it's Louis who cries. Also, Laura's dalliance with the idea of death - suicide - has a much different cast.

- Unsurprisingly, too, the novel contains several allusions to Mrs Dalloway which don't make it into the film, mostly (as far as I gathered) strengthening the parallels between Clarissa Vaughan and Woolf's Clarissa Dalloway - the appearance of the trailer within which sits an unknowable celebrity, say, in parallel to the passing motorcade in Woolf's novel, or Oliver St Ive's invitation of Sally (but not Clarissa) to lunch...of course (and this is implicit in the film, too), it's intriguing that The Hours rewrites the Sally/Clarissa relationship into a stable, long-term openly lesbian relationship (as opposed to the hints and allusions regarding the youthful relationship between Sally Seton and Clarissa Dalloway in Woolf's novel).

- Strikingly, the pathos of Woolf herself is highlighted in the film, and she is more central to its narrative. This comes through in many small ways - the drama of the confrontation with Leonard at the train station (as opposed to the gentle left-unspokenness of the novel's treatment), the empathy which Angelica seems to share with her (completely absent from novel), the return to her story at the end...

- Also, the activist Mary Krull and her relationship to Julia is omitted from the film, presumably for reasons of narrative economy (even in the context of the novel, it's interesting but scarcely necessary); similarly some of the other strands of the novel...again to prevent detracting from the Virginia/Clarissa/Laura focus.

Art, love, death, life. (What a lark! What a plunge!) And so it goes...

In terms of the film, then:

- Overall, the film has a somewhat more dramatic bent, directed, I think, at heightening the audience's responses to Virginia, Clarissa and Laura. The first of the scenes in which Clarissa and Richard confront each other in the latter's squalid apartment, for example, has an edge and a sense of simmering anger, disappointment, almost spite, which is absent from the book's treatment, which is more polite and subdued. In another example, Clarissa's breakdown in the kitchen doesn't occur in the book - instead, it's Louis who cries. Also, Laura's dalliance with the idea of death - suicide - has a much different cast.

- Unsurprisingly, too, the novel contains several allusions to Mrs Dalloway which don't make it into the film, mostly (as far as I gathered) strengthening the parallels between Clarissa Vaughan and Woolf's Clarissa Dalloway - the appearance of the trailer within which sits an unknowable celebrity, say, in parallel to the passing motorcade in Woolf's novel, or Oliver St Ive's invitation of Sally (but not Clarissa) to lunch...of course (and this is implicit in the film, too), it's intriguing that The Hours rewrites the Sally/Clarissa relationship into a stable, long-term openly lesbian relationship (as opposed to the hints and allusions regarding the youthful relationship between Sally Seton and Clarissa Dalloway in Woolf's novel).

- Strikingly, the pathos of Woolf herself is highlighted in the film, and she is more central to its narrative. This comes through in many small ways - the drama of the confrontation with Leonard at the train station (as opposed to the gentle left-unspokenness of the novel's treatment), the empathy which Angelica seems to share with her (completely absent from novel), the return to her story at the end...

- Also, the activist Mary Krull and her relationship to Julia is omitted from the film, presumably for reasons of narrative economy (even in the context of the novel, it's interesting but scarcely necessary); similarly some of the other strands of the novel...again to prevent detracting from the Virginia/Clarissa/Laura focus.

Art, love, death, life. (What a lark! What a plunge!) And so it goes...

Wednesday, November 30, 2005

The Work of Director Chris Cunningham: Directors Label vol 2

Eight music videos and a few extras. Cunningham's work is largely futuristic-looking, blue-grey metallic sheens, bright lights against shades...often rather disturbing (the ones for "Come To Daddy" and "Window Licker" must be two of the most troubling music videos ever to have achieved a mainstream release - stumbling across them for the first time during separate late-night rage watchings was fairly intense, and they still give me a small jolt today).

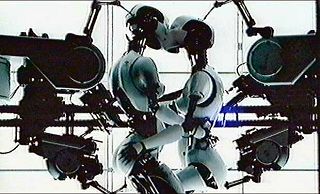

Apart from the Aphex clips, there are two pop songs whose videos are amongst my favourites - Björk's "All Is Full Of Love" (robot sex and all, it somehow fits the chugging slink of the single edit of the song perfectly; apparently Björk had asked Cunningham to make a 'white heaven' clip, and I think that it must be accounted a success on that front) and Madonna's "Frozen" (which I remember watching on early morning video tv back in the day - must've been high school - and thinking both very weird and very cool...many of the details, it turns out, are still etched in my mind). The jerky culture-shock narrative of Leftfield's "Afrika Shox" is the way that I'd have imagined the song's video would look, if I'd ever paused to imagine how the song's video would look. The one for Portishead's "Only You" is suitably moody but, rather like the song itself, doesn't really go anywhere. The Autechre one ("Second Bad Vilbel" - I hadn't heard the song before) fits the music - industrial-styled props and glitches jerking and wavering in time to the music - but is kinda boring for all that. And the Squarepusher one ("Come On My Selector" - again, I didn't know the song) is, while weird, also a bit blah.

Apart from the Aphex clips, there are two pop songs whose videos are amongst my favourites - Björk's "All Is Full Of Love" (robot sex and all, it somehow fits the chugging slink of the single edit of the song perfectly; apparently Björk had asked Cunningham to make a 'white heaven' clip, and I think that it must be accounted a success on that front) and Madonna's "Frozen" (which I remember watching on early morning video tv back in the day - must've been high school - and thinking both very weird and very cool...many of the details, it turns out, are still etched in my mind). The jerky culture-shock narrative of Leftfield's "Afrika Shox" is the way that I'd have imagined the song's video would look, if I'd ever paused to imagine how the song's video would look. The one for Portishead's "Only You" is suitably moody but, rather like the song itself, doesn't really go anywhere. The Autechre one ("Second Bad Vilbel" - I hadn't heard the song before) fits the music - industrial-styled props and glitches jerking and wavering in time to the music - but is kinda boring for all that. And the Squarepusher one ("Come On My Selector" - again, I didn't know the song) is, while weird, also a bit blah.

Apart from the Aphex clips, there are two pop songs whose videos are amongst my favourites - Björk's "All Is Full Of Love" (robot sex and all, it somehow fits the chugging slink of the single edit of the song perfectly; apparently Björk had asked Cunningham to make a 'white heaven' clip, and I think that it must be accounted a success on that front) and Madonna's "Frozen" (which I remember watching on early morning video tv back in the day - must've been high school - and thinking both very weird and very cool...many of the details, it turns out, are still etched in my mind). The jerky culture-shock narrative of Leftfield's "Afrika Shox" is the way that I'd have imagined the song's video would look, if I'd ever paused to imagine how the song's video would look. The one for Portishead's "Only You" is suitably moody but, rather like the song itself, doesn't really go anywhere. The Autechre one ("Second Bad Vilbel" - I hadn't heard the song before) fits the music - industrial-styled props and glitches jerking and wavering in time to the music - but is kinda boring for all that. And the Squarepusher one ("Come On My Selector" - again, I didn't know the song) is, while weird, also a bit blah.

Apart from the Aphex clips, there are two pop songs whose videos are amongst my favourites - Björk's "All Is Full Of Love" (robot sex and all, it somehow fits the chugging slink of the single edit of the song perfectly; apparently Björk had asked Cunningham to make a 'white heaven' clip, and I think that it must be accounted a success on that front) and Madonna's "Frozen" (which I remember watching on early morning video tv back in the day - must've been high school - and thinking both very weird and very cool...many of the details, it turns out, are still etched in my mind). The jerky culture-shock narrative of Leftfield's "Afrika Shox" is the way that I'd have imagined the song's video would look, if I'd ever paused to imagine how the song's video would look. The one for Portishead's "Only You" is suitably moody but, rather like the song itself, doesn't really go anywhere. The Autechre one ("Second Bad Vilbel" - I hadn't heard the song before) fits the music - industrial-styled props and glitches jerking and wavering in time to the music - but is kinda boring for all that. And the Squarepusher one ("Come On My Selector" - again, I didn't know the song) is, while weird, also a bit blah.

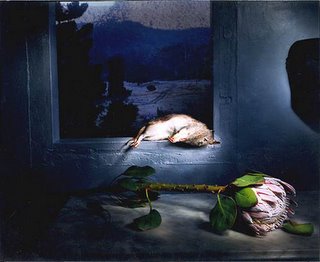

Marian Drew - "Still Lives" @ Dianne Tanzer Gallery

The premise is this: found Australian roadkill (magpies, wombats, bandicoots, possums, etc) posed and photographed as part of otherwise traditionally-composed still lives (fruit, cutlery, background landscapes, etc). Done in a way, though, which is thought-provoking without being jarringly incongruous - the writeup which brought the exhibition to my attention suggests that Drew's art 'plays up their [the dead animals'] languid beauty', and I think that that's quite true...the overall effect is one of slightly bruised prettiness rather than of shock or grotesquerie. But of course there is a striking element of the incongruous to the juxtaposition, rendered more effective by the almost stealthy way in which it intrudes itself.

There was a short video projection running on loop in the rear space of the gallery, giving some insight into the works. The most interesting part is the connection which Drew makes between our social reactions to roadkill and the presentation of food (both in images of art, and at the table itself, if I have this right) as a sign of mastery (the latter being a typically European gesture, according to her); through these works, she seeks to call these responses and practices into question.

There was a short video projection running on loop in the rear space of the gallery, giving some insight into the works. The most interesting part is the connection which Drew makes between our social reactions to roadkill and the presentation of food (both in images of art, and at the table itself, if I have this right) as a sign of mastery (the latter being a typically European gesture, according to her); through these works, she seeks to call these responses and practices into question.

I thought that it was quite neat.

Information here.

There was a short video projection running on loop in the rear space of the gallery, giving some insight into the works. The most interesting part is the connection which Drew makes between our social reactions to roadkill and the presentation of food (both in images of art, and at the table itself, if I have this right) as a sign of mastery (the latter being a typically European gesture, according to her); through these works, she seeks to call these responses and practices into question.

There was a short video projection running on loop in the rear space of the gallery, giving some insight into the works. The most interesting part is the connection which Drew makes between our social reactions to roadkill and the presentation of food (both in images of art, and at the table itself, if I have this right) as a sign of mastery (the latter being a typically European gesture, according to her); through these works, she seeks to call these responses and practices into question.I thought that it was quite neat.

Information here.

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

The Hours

Sometimes a film comes along at just the right time.

It had occurred to me that now might be the right time for me to see The Hours, having read and loved Mrs Dalloway this semester, and also becoming increasingly serious about the possibility of writing a novel myself as the days and nights stretch into summer. But I hadn't realised just how right it would turn out to be - The Hours is a gorgeous film and touched me deeply.

I think that it made a big difference that I was familiar with Mrs Dalloway, and also, I guess, that my sensitivities and sensibilities are such as to make me receptive to both book and film. In one way, The Hours is 'about' Mrs Dalloway, but it also somehow mysteriously 'feels' like Woolf's book, developing many of the same ideas and, in the process, moving me in many of the same ways. Well, it's about life, I suppose, and choices - so sad and yet ultimately hopeful. There's a clear-sightedness and a truth to it.

As a film, it's very graceful and completely involving. Feels quite literary, and I can imagine people (sophisticated film-goers at that) finding it rather slow going, but I truly didn't want it to end. Yet it ends exactly when and as it had to.

The acting is wonderful. Kidman's Woolf is tormented, needy, alluring, human - I saw echoes of myself and of many people I know in her. Julianne Moore is fragile and unbearably sad. Meryl Streep is note perfect. For all three, this was the best I've seen them. And the supports are just right - Ed Harris, Stephen Dillane (as Leonard Woolf), Claire Danes, Toni Collette (in a brief cameo), and all the others.

The choice of Philip Glass to provide the score at first struck me as being rather out of left field, but in fact works perfectly - his cyclic, mournfully pretty compositions set just the right tone and provide a link for the three stories beyond the parallels and the book Mrs Dalloway itself.

There's so much more to say, but I can't find the words to say it. I can't say it better than the film itself does.

Anyway, I suspect that 'objectively' The Hours isn't a 'great' film, whatever that means. But what can I say? It spoke to me. Sometimes a film is just right.

It had occurred to me that now might be the right time for me to see The Hours, having read and loved Mrs Dalloway this semester, and also becoming increasingly serious about the possibility of writing a novel myself as the days and nights stretch into summer. But I hadn't realised just how right it would turn out to be - The Hours is a gorgeous film and touched me deeply.

I think that it made a big difference that I was familiar with Mrs Dalloway, and also, I guess, that my sensitivities and sensibilities are such as to make me receptive to both book and film. In one way, The Hours is 'about' Mrs Dalloway, but it also somehow mysteriously 'feels' like Woolf's book, developing many of the same ideas and, in the process, moving me in many of the same ways. Well, it's about life, I suppose, and choices - so sad and yet ultimately hopeful. There's a clear-sightedness and a truth to it.

As a film, it's very graceful and completely involving. Feels quite literary, and I can imagine people (sophisticated film-goers at that) finding it rather slow going, but I truly didn't want it to end. Yet it ends exactly when and as it had to.

The acting is wonderful. Kidman's Woolf is tormented, needy, alluring, human - I saw echoes of myself and of many people I know in her. Julianne Moore is fragile and unbearably sad. Meryl Streep is note perfect. For all three, this was the best I've seen them. And the supports are just right - Ed Harris, Stephen Dillane (as Leonard Woolf), Claire Danes, Toni Collette (in a brief cameo), and all the others.

The choice of Philip Glass to provide the score at first struck me as being rather out of left field, but in fact works perfectly - his cyclic, mournfully pretty compositions set just the right tone and provide a link for the three stories beyond the parallels and the book Mrs Dalloway itself.

There's so much more to say, but I can't find the words to say it. I can't say it better than the film itself does.

Anyway, I suspect that 'objectively' The Hours isn't a 'great' film, whatever that means. But what can I say? It spoke to me. Sometimes a film is just right.

Sunday, November 27, 2005

Joseph Heller - Catch-22

I suppose that this reflects the particular circles in which I move, but certain books and authors come up in conversation over and over - The Outsider, The Great Gatsby, The Age of Innocence, Wuthering Heights, White Teeth, Foucault's Pendulum, Austen, Plath, Dostoevsky, Rushdie, Pynchon (admittedly in part because I always talk about him...), DeLillo, Eggers, Kundera, Margaret Atwood, Angela Carter, Jeanette Winterson, Peter Carey, Tim Winton...some of these were on vce syllabi and others are basically unavoidable for anyone majoring in lit (at least at Melb Uni), but still they must have something in order to stand out from the many others of which or whom the same could be said.

Catch-22 is one such - a lot of people have read this book, and many of them have loved it (I'm not sure if I've remembered this right, but I think that it was Ben S's favourite book, at least as of a few years ago). So I'd always kind of intended to read it but never had any particular impetus to do so; having finally read the thing over the last few days, I've been wondering why no one ever told me how ridiculously funny the book is...I haven't laughed so much while reading a novel in ages, in cafes and on public transport as much as at home by myself.

'Ridiculously' is right, for the humour is deliberately absurdist. Much of it's slapstick - one passage which sticks in my mind is that in which Yossarian and Dunbar pull rank by telling a series of other patients (including one A. Fortiori) to 'Screw', culminating in Yossarian's run-in with Nurse Cramer - but there's a deeper purpose to the pratfalls and general grotesquerie, for it all highlights the pointlessness of war and bureaucracy (witness the inescapable influence of Wintergreen's low level malevolence, say).

There are quite a lot of loose ends - to name just a few, Doc Daneeka is left to languish as a dead man without there being any particular resolution of his fate, General Dreedle just disappears from the scene once he's replaced by General Peckem, nothing ever really happens in relation to Major --- de Coverley (though that last may be apt in terms of the figure's general inscrutability), and does Chief White Halfoat end up dying or not? - but perhaps that's apt...the narrative cycles and repeats itself, but this endless circularity ('Catch-22'!) needn't - and, in Heller's universe, doesn't - imply resolution or completion. Events are oriented around the logic of the titular 'Catch-22', which encapsulates the absurdity of it all, appearing and ramifying in guises and situations which are ever-changing but somehow always the same.

It's striking, too, that in some ways the novel evinces quite a conventional progression - the characters are introduced, we begin to sympathise with them (with figures like Yossarian and the Chaplain in particular, who eventually prove to be the (anti-)heroes of the book), and then, in order to make the author's point, they begin dying (Cathcart, Korn, Milo, and others of their ilk are, of course, insulated from any such risk, but the McWatts and Natelys begin falling with an indecent haste in the final sections of the book). They're not really grotesque characters, but they find themselves in grotesque situations (eg, war) - that reminds me of Pynchon's aphorism about paranoids (in Gravity's Rainbow?) which, paraphrased, goes something like 'paranoids are paranoids not because they're paranoid, but because they, fucking idiots, keep putting themselves in paranoid situations', but then one never really sympathises with Pynchon's characters, only identifies with the pathos of their Situations.

Catch-22 does remind me of Pynchon, and also of Dr Strangelove - these are easy comparisons, but none the less revealing for that ease, I don't think. But to me it seems to have more of a centre - a core - than Pynchon's work (not least in the forms of subjectivity and thematic development it evinces, and in its close, specific targeting of the effects of war) and more of a wildness, an unhingedness which is perhaps the prerogative of literature (as opposed to film), than Strangelove. Easy to read, but there's plenty going on.

Catch-22 is one such - a lot of people have read this book, and many of them have loved it (I'm not sure if I've remembered this right, but I think that it was Ben S's favourite book, at least as of a few years ago). So I'd always kind of intended to read it but never had any particular impetus to do so; having finally read the thing over the last few days, I've been wondering why no one ever told me how ridiculously funny the book is...I haven't laughed so much while reading a novel in ages, in cafes and on public transport as much as at home by myself.

'Ridiculously' is right, for the humour is deliberately absurdist. Much of it's slapstick - one passage which sticks in my mind is that in which Yossarian and Dunbar pull rank by telling a series of other patients (including one A. Fortiori) to 'Screw', culminating in Yossarian's run-in with Nurse Cramer - but there's a deeper purpose to the pratfalls and general grotesquerie, for it all highlights the pointlessness of war and bureaucracy (witness the inescapable influence of Wintergreen's low level malevolence, say).

There are quite a lot of loose ends - to name just a few, Doc Daneeka is left to languish as a dead man without there being any particular resolution of his fate, General Dreedle just disappears from the scene once he's replaced by General Peckem, nothing ever really happens in relation to Major --- de Coverley (though that last may be apt in terms of the figure's general inscrutability), and does Chief White Halfoat end up dying or not? - but perhaps that's apt...the narrative cycles and repeats itself, but this endless circularity ('Catch-22'!) needn't - and, in Heller's universe, doesn't - imply resolution or completion. Events are oriented around the logic of the titular 'Catch-22', which encapsulates the absurdity of it all, appearing and ramifying in guises and situations which are ever-changing but somehow always the same.

It's striking, too, that in some ways the novel evinces quite a conventional progression - the characters are introduced, we begin to sympathise with them (with figures like Yossarian and the Chaplain in particular, who eventually prove to be the (anti-)heroes of the book), and then, in order to make the author's point, they begin dying (Cathcart, Korn, Milo, and others of their ilk are, of course, insulated from any such risk, but the McWatts and Natelys begin falling with an indecent haste in the final sections of the book). They're not really grotesque characters, but they find themselves in grotesque situations (eg, war) - that reminds me of Pynchon's aphorism about paranoids (in Gravity's Rainbow?) which, paraphrased, goes something like 'paranoids are paranoids not because they're paranoid, but because they, fucking idiots, keep putting themselves in paranoid situations', but then one never really sympathises with Pynchon's characters, only identifies with the pathos of their Situations.

Catch-22 does remind me of Pynchon, and also of Dr Strangelove - these are easy comparisons, but none the less revealing for that ease, I don't think. But to me it seems to have more of a centre - a core - than Pynchon's work (not least in the forms of subjectivity and thematic development it evinces, and in its close, specific targeting of the effects of war) and more of a wildness, an unhingedness which is perhaps the prerogative of literature (as opposed to film), than Strangelove. Easy to read, but there's plenty going on.

Thursday, November 24, 2005

Hilary and Jackie

An emotionally involving film, this - I spent nearly the whole time with my arms wrapped around myself or with one hand pressed to my forehead in a kind of warding-off gesture, and realised at a couple of points that I had almost forgotten to breathe. Sometimes films take me like that, and I think that it mainly has to do with my sympathising with the characters - I squirm and wince and feel awkward and embarrassed for them...it's a very immediate experience, and I don't think it depends at all on being able to imagine myself in their shoes - just the depiction itself is enough.

Actually, the last film which provoked this sort of response in me was Punch-Drunk Love, and it may not be entirely coincidental that Emily Watson was also in that one; she's an astonishingly good actor, and I can still vividly recall how much of a punch in the guts Breaking The Waves - the first thing I saw her in - was when I watched it years ago (much as I loved it, I haven't been able to bear the thought of watching the film since). In Hilary and Jackie, as Jacqueline du Pré, she's utterly compelling - you can't take your eyes off her, and yet some of her scenes are almost unbearable to watch because of the awkwardness and rawness of her character. And Rachel Griffiths is just as good, as her sister, Hilary - in every way, she's just exactly right...both ring completely true.

This film could easily have been boring (because it's so unassuming in its conception) or tritely melodramatic (because the feelings and relationships are so deeply felt and sometimes extravagantly expressed), but both performances and screenplay are perfectly pitched and so instead it's simply lovely...one of those films that, in its modest, poignant way, is about nothing more nor less than what it is to be human and alive.

Actually, the last film which provoked this sort of response in me was Punch-Drunk Love, and it may not be entirely coincidental that Emily Watson was also in that one; she's an astonishingly good actor, and I can still vividly recall how much of a punch in the guts Breaking The Waves - the first thing I saw her in - was when I watched it years ago (much as I loved it, I haven't been able to bear the thought of watching the film since). In Hilary and Jackie, as Jacqueline du Pré, she's utterly compelling - you can't take your eyes off her, and yet some of her scenes are almost unbearable to watch because of the awkwardness and rawness of her character. And Rachel Griffiths is just as good, as her sister, Hilary - in every way, she's just exactly right...both ring completely true.

This film could easily have been boring (because it's so unassuming in its conception) or tritely melodramatic (because the feelings and relationships are so deeply felt and sometimes extravagantly expressed), but both performances and screenplay are perfectly pitched and so instead it's simply lovely...one of those films that, in its modest, poignant way, is about nothing more nor less than what it is to be human and alive.

Wednesday, November 23, 2005

The Thackery T. Lambshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric & Discredited Diseases edited by Jeff Vandermeer and Mark Roberts

Okay, squeamish isn't quite the right word, but I can be a...uh...call it 'physically sensitive' reader. A good example of this was the fashion in which, when I was reading Anne Rice's Interview with the Vampire series, back in the day, I often noticed that a large vein at the side of my throat would start throbbing in sympathy after a while - I don't know if it was actually the jugular, but even if it wasn't, quite possibly all that matters is that I thought that it was. And reading descriptions of throats being cut or wrists slit often make me physically uncomfortable to the point that I have to stop reading for a while and think hard about something else (the description of the murder early in Kate Atkinson's latest, Case Histories, had that effect on me).

For that reason, I found that I wasn't able to read too much of this Pocket Guide at any one sitting. See, it's ostensibly a medical guide to, as its title suggests, a variety of diseases which fall somewhat beyond the compass of orthodox diagnosis. Its major part is comprised of individual entries for particular diseases (submitted by a long roll call of worthies including Miéville, Moorcock, Gaiman and Alan Moore), ranging from: Ballistic Organ Syndrome, which: "manifests as a sudden, explosive discharge of one or more bodily organs at high velocity; this exit may be accompanied by some pain"; to Inverted Drowning Syndrome; to Mongolian Death Worm Infestation, to Postal Carriers' Brain Fluke Syndrome, propagated by flukes whose mode of dissemination is so elaborate and dependent on fortuities that they seem to be "performing an extinction-defying trapeze act purely for the sake of impressing other parasites" (with accompanying footnote to a book entitled Vanity: Watch Spring of Evolution); to Reverse Pinocchio Syndrome, in which people who tell a great number of lies are eventually afflicted by the development of a black hole in one nostril once it has developed its own gravity, eventually resulting in the skull being sucked into the black hole itself. Scores of them, each detailed in terms of symptoms, first known case, treatment and cures, etc. Gross, and funny.

Also includes a publishing history of the Pocket Guide (this is supposedly the 83rd edition) complete with reproductions of covers and entries from past editions, an 'obscure medical history of the twentieth century', in which phenomena including but far from limited to the career and demise of Freud, Stalingrad, the Kennedy assassination, and AIDS are explained in terms of the diseases enumerated, various reminiscences written by other doctors who have encountered the formidable Lambshead in the course of his storied career, an introduction by the centenarian Lambshead himself, and various other odds and ends, including 'a disease guide benediction for the health & safety of all contributors, readers, and (sympathetic) reviewers', which concludes (and this made me laugh out loud - too much philosophy for me lately, obviously):

So obviously all of this is made up, from the diseases themselves to the spurious biography and historiography of Lambshead and the Guide. On one level, it satirises the pretension of medical guides and the language and style in which they're written. But that's really just a launching-pad for some very postmodern imaginative pyrotechnics, as many of the disease entries are written by authors who've apparently been infected by the diseases themselves, other of the diseases can be transmitted by being read about, and self-referentiality, inter-textuality (Borges - a natural touchstone for this kind of speculative writing - is mentioned as often as made-up legends of the eccentric disease field), and so on. Definitely recommendable, though some might find its general attitude of too-clever-for-its-own-goodness to be a bit annoying.

Some information here.

For that reason, I found that I wasn't able to read too much of this Pocket Guide at any one sitting. See, it's ostensibly a medical guide to, as its title suggests, a variety of diseases which fall somewhat beyond the compass of orthodox diagnosis. Its major part is comprised of individual entries for particular diseases (submitted by a long roll call of worthies including Miéville, Moorcock, Gaiman and Alan Moore), ranging from: Ballistic Organ Syndrome, which: "manifests as a sudden, explosive discharge of one or more bodily organs at high velocity; this exit may be accompanied by some pain"; to Inverted Drowning Syndrome; to Mongolian Death Worm Infestation, to Postal Carriers' Brain Fluke Syndrome, propagated by flukes whose mode of dissemination is so elaborate and dependent on fortuities that they seem to be "performing an extinction-defying trapeze act purely for the sake of impressing other parasites" (with accompanying footnote to a book entitled Vanity: Watch Spring of Evolution); to Reverse Pinocchio Syndrome, in which people who tell a great number of lies are eventually afflicted by the development of a black hole in one nostril once it has developed its own gravity, eventually resulting in the skull being sucked into the black hole itself. Scores of them, each detailed in terms of symptoms, first known case, treatment and cures, etc. Gross, and funny.

Also includes a publishing history of the Pocket Guide (this is supposedly the 83rd edition) complete with reproductions of covers and entries from past editions, an 'obscure medical history of the twentieth century', in which phenomena including but far from limited to the career and demise of Freud, Stalingrad, the Kennedy assassination, and AIDS are explained in terms of the diseases enumerated, various reminiscences written by other doctors who have encountered the formidable Lambshead in the course of his storied career, an introduction by the centenarian Lambshead himself, and various other odds and ends, including 'a disease guide benediction for the health & safety of all contributors, readers, and (sympathetic) reviewers', which concludes (and this made me laugh out loud - too much philosophy for me lately, obviously):

Z is for Zeno's paradoxysm, which fills us with misgiving,

By infinitely tiny steps it deadens but won't kill.

As no one could be sure if Aunt Augusta was still living

We propped her in her favorite chair to wait. She's waiting still.

So obviously all of this is made up, from the diseases themselves to the spurious biography and historiography of Lambshead and the Guide. On one level, it satirises the pretension of medical guides and the language and style in which they're written. But that's really just a launching-pad for some very postmodern imaginative pyrotechnics, as many of the disease entries are written by authors who've apparently been infected by the diseases themselves, other of the diseases can be transmitted by being read about, and self-referentiality, inter-textuality (Borges - a natural touchstone for this kind of speculative writing - is mentioned as often as made-up legends of the eccentric disease field), and so on. Definitely recommendable, though some might find its general attitude of too-clever-for-its-own-goodness to be a bit annoying.

Some information here.

Van Helsing

Gosh, this is a really bad movie. It has precisely two redeeming features: great set design, and comic relief from David Wenham. Apart from that, unremittingly awful - basically boring and frequently so bad it's laughable. Two hours of my life that would've been much better spent wrapped up in books.

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

The Cardigans - First Band on the Moon

Cool Scandinavian indie-pop with a bit of an edge, circa '96. This is the one with "Lovefool" (not to mention a Black Sabbath cover). "Lovefool" still a joy after all these years and despite constant listening on R+J soundtrack, "Great Divide" nice in a chimey fairground "Mike Mills" (as in the Air song) kind of way, and a couple of others deliciously off-kilter and catchy, though most of the songs on this record can't hold a candle to the band's simply splendid (and splendidly titled) current single, "I Need Some Fine Wine And You, You Need To Be Nicer".

Another list: Key early books

And while I'm excavating my past as a reader, here's my attempt at recalling and listing the books which left a deep impression when I read them in primary school (no doubt I'll miss many, but anyway...):

- The Green Wind by Thurley Fowler. This just might have been the first 'proper' book that I really loved and treasured. Looking back, it's easy to see why I was drawn to the central character, Jennifer - a sarcastic, prickly, but sympathetically-rendered 11yo type with aspirations of being a writer who feels herself to be different from everyone else - but at the time, all I knew was that the book spoke to me. Years later, I was pleasantly surprised when I learnt that Penny, one of my best friends from uni, had felt similarly about the book at the corresponding time in her life - indeed, being female and approximately red-haired, and having grown up in the country, she's much more of a Jennifer type than I.

- Master of the Grove by Victor Kelleher. Might well have been the book which first opened my eyes to the wonder that literature can bring.

- Space Demons by Gillian Rubenstein. This one just caught my imagination and wouldn't let go. I dreamt about it - and its sequel, Skymaze, too.

- Gone With The Wind by Margaret Mitchell. Pulled my mum's tatty old copy from the book shelf one woozy summer day and lost the next few weeks to its reading, completely wrapped up in its drowsy charms; have re-read several times since (most recently a couple of years back - I wrote about it on open diary at the time), finding it to be almost a completely different and new book each time.

- To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee. I'm not 100% sure, but I think that this was the book which first planted the thought that I might want to be a lawyer. It really stirred me up when I read it, even though I'm sure that I didn't grasp half of what was going on. For some reason it came up in a scholarship interview I went to in grade 6 (for year 7 onwards) at Melbourne Grammar, and I remember the headmaster asking what I thought about capital punishment...heavens know what I answered!

- Small Gods by Terry Pratchett. The first Pratchett book I read and, for better or for worse (I'm much inclined to think 'better'), the beginning of a very long and deep engagement indeed.

I suspect there were at least one or two others, but those are the ones which spring to mind right now.

- The Green Wind by Thurley Fowler. This just might have been the first 'proper' book that I really loved and treasured. Looking back, it's easy to see why I was drawn to the central character, Jennifer - a sarcastic, prickly, but sympathetically-rendered 11yo type with aspirations of being a writer who feels herself to be different from everyone else - but at the time, all I knew was that the book spoke to me. Years later, I was pleasantly surprised when I learnt that Penny, one of my best friends from uni, had felt similarly about the book at the corresponding time in her life - indeed, being female and approximately red-haired, and having grown up in the country, she's much more of a Jennifer type than I.

- Master of the Grove by Victor Kelleher. Might well have been the book which first opened my eyes to the wonder that literature can bring.

- Space Demons by Gillian Rubenstein. This one just caught my imagination and wouldn't let go. I dreamt about it - and its sequel, Skymaze, too.

- Gone With The Wind by Margaret Mitchell. Pulled my mum's tatty old copy from the book shelf one woozy summer day and lost the next few weeks to its reading, completely wrapped up in its drowsy charms; have re-read several times since (most recently a couple of years back - I wrote about it on open diary at the time), finding it to be almost a completely different and new book each time.

- To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee. I'm not 100% sure, but I think that this was the book which first planted the thought that I might want to be a lawyer. It really stirred me up when I read it, even though I'm sure that I didn't grasp half of what was going on. For some reason it came up in a scholarship interview I went to in grade 6 (for year 7 onwards) at Melbourne Grammar, and I remember the headmaster asking what I thought about capital punishment...heavens know what I answered!

- Small Gods by Terry Pratchett. The first Pratchett book I read and, for better or for worse (I'm much inclined to think 'better'), the beginning of a very long and deep engagement indeed.

I suspect there were at least one or two others, but those are the ones which spring to mind right now.

George R R Martin - A Game of Thrones, A Clash of Kings & A Storm of Swords

Having drugged myself into a familiar, dazed drowsiness with these three hefty volumes for the better part of the time since that last paper was handed in, I've been wondering just why I read (and re-read) fantasy. The genre was pretty significant in the development of my reading habits - I remember Victor Kelleher's Master of the Grove making a huge impression at some point which must've been no later than grade 4, since I have a distinct memory of reading it in the library of my old primary school, and at around that time there were also those godawful 'choose your own adventure'-type books (I can't remember the series title, but they had bright green covers and were written by Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone [sp?])...and then, I think, it was David Eddings (and Terry Pratchett) from grade 6 and Stephen Donaldson the year after, in AAP (again, distinct memory of reading and being amazed by Lord Foul's Bane on the way up to camp). I'm pretty sure that Eddings was the first author whose books I was reading from the 'adult' (as opposed to 'junior'/'teenage') section of the library...somewhere in those early years I also read Tolkien and was suitably awed.

At the time, and even (especially?) through high school, I loved the genre because it was so epic - it held the promise of richer, more magical worlds, and, at its best, had such heft and sweep, and my teenage years were stormy and black enough (or, at least, so they seemed at the time, which is of course what counts) that the sheer escapism must've been alluring (though I don't think I ever thought of it in quite those terms). It's really hard to articulate, and I don't think I could've done so properly even at the time when I really felt it.

The thing is, though, that I don't feel it any more, not really, which brings me back to where I started: why do I read these books? I guess that in part it's indolence - they're so easy to read, and an enjoyable escape (even if they no longer make my spine tingle, or at least not as much as they used to), and if I'm going to read anyway, why not? Not really a very good answer, but maybe it wasn't a very good question in the first place.

As to the "Song of Ice and Fire" series itself: Well, this one I only read last year (well, read up to its current state, anyway - it's not yet finished by the author), I think, or the year before at the very earliest, and it struck me at the time as one of the best epic fantasy series out there. Simply put, it's gripping. It has gravitas and the all-important epic sweep, but it also has well-drawn, interesting characters. There's political intrigue a-plenty - much moving of pieces around the board (fates of nations and individual consciences both at stake), unexpected reversals of luck and loyalty, marriages promised and broken for the sake of alliances...the great families bound to one another by a complex merry-go-round of arranged marriages, children of enemies warded in foreign lands, imprisonments, ransoms, escapes, recaptures, characters flung together in strange configurations as they jostle and are jostled for position. But the battle and action scenes are also well done, and Martin doesn't stint on the characterisation either (witness Catelyn's complex emotions, or Tyrion, or the arc followed by Jaime Lannister, to name just a few), nor on the surprises (the first time I read these books, I was astonished when Eddard Stark died, and again when Robb met the same fate). Nor does he go overboard with the magical or fantastic elements - they become gradually more prominent as the series goes on. One of the glowing comments on the back of the books references the War of the Roses, and I reckon that's exactly right. On this re-read, it's slightly less excellent (unsurprisingly) but still pretty darn good.