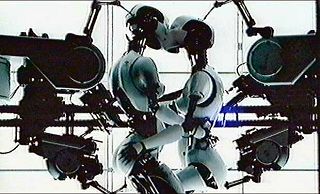

Apart from the Aphex clips, there are two pop songs whose videos are amongst my favourites - Björk's "All Is Full Of Love" (robot sex and all, it somehow fits the chugging slink of the single edit of the song perfectly; apparently Björk had asked Cunningham to make a 'white heaven' clip, and I think that it must be accounted a success on that front) and Madonna's "Frozen" (which I remember watching on early morning video tv back in the day - must've been high school - and thinking both very weird and very cool...many of the details, it turns out, are still etched in my mind). The jerky culture-shock narrative of Leftfield's "Afrika Shox" is the way that I'd have imagined the song's video would look, if I'd ever paused to imagine how the song's video would look. The one for Portishead's "Only You" is suitably moody but, rather like the song itself, doesn't really go anywhere. The Autechre one ("Second Bad Vilbel" - I hadn't heard the song before) fits the music - industrial-styled props and glitches jerking and wavering in time to the music - but is kinda boring for all that. And the Squarepusher one ("Come On My Selector" - again, I didn't know the song) is, while weird, also a bit blah.

Apart from the Aphex clips, there are two pop songs whose videos are amongst my favourites - Björk's "All Is Full Of Love" (robot sex and all, it somehow fits the chugging slink of the single edit of the song perfectly; apparently Björk had asked Cunningham to make a 'white heaven' clip, and I think that it must be accounted a success on that front) and Madonna's "Frozen" (which I remember watching on early morning video tv back in the day - must've been high school - and thinking both very weird and very cool...many of the details, it turns out, are still etched in my mind). The jerky culture-shock narrative of Leftfield's "Afrika Shox" is the way that I'd have imagined the song's video would look, if I'd ever paused to imagine how the song's video would look. The one for Portishead's "Only You" is suitably moody but, rather like the song itself, doesn't really go anywhere. The Autechre one ("Second Bad Vilbel" - I hadn't heard the song before) fits the music - industrial-styled props and glitches jerking and wavering in time to the music - but is kinda boring for all that. And the Squarepusher one ("Come On My Selector" - again, I didn't know the song) is, while weird, also a bit blah.

Wednesday, November 30, 2005

The Work of Director Chris Cunningham: Directors Label vol 2

Eight music videos and a few extras. Cunningham's work is largely futuristic-looking, blue-grey metallic sheens, bright lights against shades...often rather disturbing (the ones for "Come To Daddy" and "Window Licker" must be two of the most troubling music videos ever to have achieved a mainstream release - stumbling across them for the first time during separate late-night rage watchings was fairly intense, and they still give me a small jolt today).

Apart from the Aphex clips, there are two pop songs whose videos are amongst my favourites - Björk's "All Is Full Of Love" (robot sex and all, it somehow fits the chugging slink of the single edit of the song perfectly; apparently Björk had asked Cunningham to make a 'white heaven' clip, and I think that it must be accounted a success on that front) and Madonna's "Frozen" (which I remember watching on early morning video tv back in the day - must've been high school - and thinking both very weird and very cool...many of the details, it turns out, are still etched in my mind). The jerky culture-shock narrative of Leftfield's "Afrika Shox" is the way that I'd have imagined the song's video would look, if I'd ever paused to imagine how the song's video would look. The one for Portishead's "Only You" is suitably moody but, rather like the song itself, doesn't really go anywhere. The Autechre one ("Second Bad Vilbel" - I hadn't heard the song before) fits the music - industrial-styled props and glitches jerking and wavering in time to the music - but is kinda boring for all that. And the Squarepusher one ("Come On My Selector" - again, I didn't know the song) is, while weird, also a bit blah.

Apart from the Aphex clips, there are two pop songs whose videos are amongst my favourites - Björk's "All Is Full Of Love" (robot sex and all, it somehow fits the chugging slink of the single edit of the song perfectly; apparently Björk had asked Cunningham to make a 'white heaven' clip, and I think that it must be accounted a success on that front) and Madonna's "Frozen" (which I remember watching on early morning video tv back in the day - must've been high school - and thinking both very weird and very cool...many of the details, it turns out, are still etched in my mind). The jerky culture-shock narrative of Leftfield's "Afrika Shox" is the way that I'd have imagined the song's video would look, if I'd ever paused to imagine how the song's video would look. The one for Portishead's "Only You" is suitably moody but, rather like the song itself, doesn't really go anywhere. The Autechre one ("Second Bad Vilbel" - I hadn't heard the song before) fits the music - industrial-styled props and glitches jerking and wavering in time to the music - but is kinda boring for all that. And the Squarepusher one ("Come On My Selector" - again, I didn't know the song) is, while weird, also a bit blah.

Apart from the Aphex clips, there are two pop songs whose videos are amongst my favourites - Björk's "All Is Full Of Love" (robot sex and all, it somehow fits the chugging slink of the single edit of the song perfectly; apparently Björk had asked Cunningham to make a 'white heaven' clip, and I think that it must be accounted a success on that front) and Madonna's "Frozen" (which I remember watching on early morning video tv back in the day - must've been high school - and thinking both very weird and very cool...many of the details, it turns out, are still etched in my mind). The jerky culture-shock narrative of Leftfield's "Afrika Shox" is the way that I'd have imagined the song's video would look, if I'd ever paused to imagine how the song's video would look. The one for Portishead's "Only You" is suitably moody but, rather like the song itself, doesn't really go anywhere. The Autechre one ("Second Bad Vilbel" - I hadn't heard the song before) fits the music - industrial-styled props and glitches jerking and wavering in time to the music - but is kinda boring for all that. And the Squarepusher one ("Come On My Selector" - again, I didn't know the song) is, while weird, also a bit blah.

Apart from the Aphex clips, there are two pop songs whose videos are amongst my favourites - Björk's "All Is Full Of Love" (robot sex and all, it somehow fits the chugging slink of the single edit of the song perfectly; apparently Björk had asked Cunningham to make a 'white heaven' clip, and I think that it must be accounted a success on that front) and Madonna's "Frozen" (which I remember watching on early morning video tv back in the day - must've been high school - and thinking both very weird and very cool...many of the details, it turns out, are still etched in my mind). The jerky culture-shock narrative of Leftfield's "Afrika Shox" is the way that I'd have imagined the song's video would look, if I'd ever paused to imagine how the song's video would look. The one for Portishead's "Only You" is suitably moody but, rather like the song itself, doesn't really go anywhere. The Autechre one ("Second Bad Vilbel" - I hadn't heard the song before) fits the music - industrial-styled props and glitches jerking and wavering in time to the music - but is kinda boring for all that. And the Squarepusher one ("Come On My Selector" - again, I didn't know the song) is, while weird, also a bit blah.

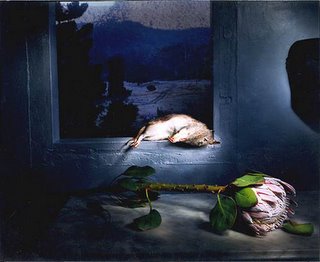

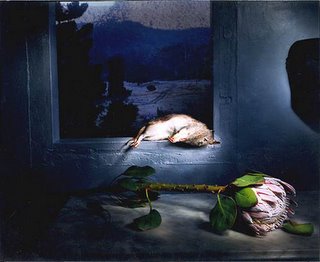

Marian Drew - "Still Lives" @ Dianne Tanzer Gallery

The premise is this: found Australian roadkill (magpies, wombats, bandicoots, possums, etc) posed and photographed as part of otherwise traditionally-composed still lives (fruit, cutlery, background landscapes, etc). Done in a way, though, which is thought-provoking without being jarringly incongruous - the writeup which brought the exhibition to my attention suggests that Drew's art 'plays up their [the dead animals'] languid beauty', and I think that that's quite true...the overall effect is one of slightly bruised prettiness rather than of shock or grotesquerie. But of course there is a striking element of the incongruous to the juxtaposition, rendered more effective by the almost stealthy way in which it intrudes itself.

There was a short video projection running on loop in the rear space of the gallery, giving some insight into the works. The most interesting part is the connection which Drew makes between our social reactions to roadkill and the presentation of food (both in images of art, and at the table itself, if I have this right) as a sign of mastery (the latter being a typically European gesture, according to her); through these works, she seeks to call these responses and practices into question.

There was a short video projection running on loop in the rear space of the gallery, giving some insight into the works. The most interesting part is the connection which Drew makes between our social reactions to roadkill and the presentation of food (both in images of art, and at the table itself, if I have this right) as a sign of mastery (the latter being a typically European gesture, according to her); through these works, she seeks to call these responses and practices into question.

I thought that it was quite neat.

Information here.

There was a short video projection running on loop in the rear space of the gallery, giving some insight into the works. The most interesting part is the connection which Drew makes between our social reactions to roadkill and the presentation of food (both in images of art, and at the table itself, if I have this right) as a sign of mastery (the latter being a typically European gesture, according to her); through these works, she seeks to call these responses and practices into question.

There was a short video projection running on loop in the rear space of the gallery, giving some insight into the works. The most interesting part is the connection which Drew makes between our social reactions to roadkill and the presentation of food (both in images of art, and at the table itself, if I have this right) as a sign of mastery (the latter being a typically European gesture, according to her); through these works, she seeks to call these responses and practices into question.I thought that it was quite neat.

Information here.

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

The Hours

Sometimes a film comes along at just the right time.

It had occurred to me that now might be the right time for me to see The Hours, having read and loved Mrs Dalloway this semester, and also becoming increasingly serious about the possibility of writing a novel myself as the days and nights stretch into summer. But I hadn't realised just how right it would turn out to be - The Hours is a gorgeous film and touched me deeply.

I think that it made a big difference that I was familiar with Mrs Dalloway, and also, I guess, that my sensitivities and sensibilities are such as to make me receptive to both book and film. In one way, The Hours is 'about' Mrs Dalloway, but it also somehow mysteriously 'feels' like Woolf's book, developing many of the same ideas and, in the process, moving me in many of the same ways. Well, it's about life, I suppose, and choices - so sad and yet ultimately hopeful. There's a clear-sightedness and a truth to it.

As a film, it's very graceful and completely involving. Feels quite literary, and I can imagine people (sophisticated film-goers at that) finding it rather slow going, but I truly didn't want it to end. Yet it ends exactly when and as it had to.

The acting is wonderful. Kidman's Woolf is tormented, needy, alluring, human - I saw echoes of myself and of many people I know in her. Julianne Moore is fragile and unbearably sad. Meryl Streep is note perfect. For all three, this was the best I've seen them. And the supports are just right - Ed Harris, Stephen Dillane (as Leonard Woolf), Claire Danes, Toni Collette (in a brief cameo), and all the others.

The choice of Philip Glass to provide the score at first struck me as being rather out of left field, but in fact works perfectly - his cyclic, mournfully pretty compositions set just the right tone and provide a link for the three stories beyond the parallels and the book Mrs Dalloway itself.

There's so much more to say, but I can't find the words to say it. I can't say it better than the film itself does.

Anyway, I suspect that 'objectively' The Hours isn't a 'great' film, whatever that means. But what can I say? It spoke to me. Sometimes a film is just right.

It had occurred to me that now might be the right time for me to see The Hours, having read and loved Mrs Dalloway this semester, and also becoming increasingly serious about the possibility of writing a novel myself as the days and nights stretch into summer. But I hadn't realised just how right it would turn out to be - The Hours is a gorgeous film and touched me deeply.

I think that it made a big difference that I was familiar with Mrs Dalloway, and also, I guess, that my sensitivities and sensibilities are such as to make me receptive to both book and film. In one way, The Hours is 'about' Mrs Dalloway, but it also somehow mysteriously 'feels' like Woolf's book, developing many of the same ideas and, in the process, moving me in many of the same ways. Well, it's about life, I suppose, and choices - so sad and yet ultimately hopeful. There's a clear-sightedness and a truth to it.

As a film, it's very graceful and completely involving. Feels quite literary, and I can imagine people (sophisticated film-goers at that) finding it rather slow going, but I truly didn't want it to end. Yet it ends exactly when and as it had to.

The acting is wonderful. Kidman's Woolf is tormented, needy, alluring, human - I saw echoes of myself and of many people I know in her. Julianne Moore is fragile and unbearably sad. Meryl Streep is note perfect. For all three, this was the best I've seen them. And the supports are just right - Ed Harris, Stephen Dillane (as Leonard Woolf), Claire Danes, Toni Collette (in a brief cameo), and all the others.

The choice of Philip Glass to provide the score at first struck me as being rather out of left field, but in fact works perfectly - his cyclic, mournfully pretty compositions set just the right tone and provide a link for the three stories beyond the parallels and the book Mrs Dalloway itself.

There's so much more to say, but I can't find the words to say it. I can't say it better than the film itself does.

Anyway, I suspect that 'objectively' The Hours isn't a 'great' film, whatever that means. But what can I say? It spoke to me. Sometimes a film is just right.

Sunday, November 27, 2005

Joseph Heller - Catch-22

I suppose that this reflects the particular circles in which I move, but certain books and authors come up in conversation over and over - The Outsider, The Great Gatsby, The Age of Innocence, Wuthering Heights, White Teeth, Foucault's Pendulum, Austen, Plath, Dostoevsky, Rushdie, Pynchon (admittedly in part because I always talk about him...), DeLillo, Eggers, Kundera, Margaret Atwood, Angela Carter, Jeanette Winterson, Peter Carey, Tim Winton...some of these were on vce syllabi and others are basically unavoidable for anyone majoring in lit (at least at Melb Uni), but still they must have something in order to stand out from the many others of which or whom the same could be said.

Catch-22 is one such - a lot of people have read this book, and many of them have loved it (I'm not sure if I've remembered this right, but I think that it was Ben S's favourite book, at least as of a few years ago). So I'd always kind of intended to read it but never had any particular impetus to do so; having finally read the thing over the last few days, I've been wondering why no one ever told me how ridiculously funny the book is...I haven't laughed so much while reading a novel in ages, in cafes and on public transport as much as at home by myself.

'Ridiculously' is right, for the humour is deliberately absurdist. Much of it's slapstick - one passage which sticks in my mind is that in which Yossarian and Dunbar pull rank by telling a series of other patients (including one A. Fortiori) to 'Screw', culminating in Yossarian's run-in with Nurse Cramer - but there's a deeper purpose to the pratfalls and general grotesquerie, for it all highlights the pointlessness of war and bureaucracy (witness the inescapable influence of Wintergreen's low level malevolence, say).

There are quite a lot of loose ends - to name just a few, Doc Daneeka is left to languish as a dead man without there being any particular resolution of his fate, General Dreedle just disappears from the scene once he's replaced by General Peckem, nothing ever really happens in relation to Major --- de Coverley (though that last may be apt in terms of the figure's general inscrutability), and does Chief White Halfoat end up dying or not? - but perhaps that's apt...the narrative cycles and repeats itself, but this endless circularity ('Catch-22'!) needn't - and, in Heller's universe, doesn't - imply resolution or completion. Events are oriented around the logic of the titular 'Catch-22', which encapsulates the absurdity of it all, appearing and ramifying in guises and situations which are ever-changing but somehow always the same.

It's striking, too, that in some ways the novel evinces quite a conventional progression - the characters are introduced, we begin to sympathise with them (with figures like Yossarian and the Chaplain in particular, who eventually prove to be the (anti-)heroes of the book), and then, in order to make the author's point, they begin dying (Cathcart, Korn, Milo, and others of their ilk are, of course, insulated from any such risk, but the McWatts and Natelys begin falling with an indecent haste in the final sections of the book). They're not really grotesque characters, but they find themselves in grotesque situations (eg, war) - that reminds me of Pynchon's aphorism about paranoids (in Gravity's Rainbow?) which, paraphrased, goes something like 'paranoids are paranoids not because they're paranoid, but because they, fucking idiots, keep putting themselves in paranoid situations', but then one never really sympathises with Pynchon's characters, only identifies with the pathos of their Situations.

Catch-22 does remind me of Pynchon, and also of Dr Strangelove - these are easy comparisons, but none the less revealing for that ease, I don't think. But to me it seems to have more of a centre - a core - than Pynchon's work (not least in the forms of subjectivity and thematic development it evinces, and in its close, specific targeting of the effects of war) and more of a wildness, an unhingedness which is perhaps the prerogative of literature (as opposed to film), than Strangelove. Easy to read, but there's plenty going on.

Catch-22 is one such - a lot of people have read this book, and many of them have loved it (I'm not sure if I've remembered this right, but I think that it was Ben S's favourite book, at least as of a few years ago). So I'd always kind of intended to read it but never had any particular impetus to do so; having finally read the thing over the last few days, I've been wondering why no one ever told me how ridiculously funny the book is...I haven't laughed so much while reading a novel in ages, in cafes and on public transport as much as at home by myself.

'Ridiculously' is right, for the humour is deliberately absurdist. Much of it's slapstick - one passage which sticks in my mind is that in which Yossarian and Dunbar pull rank by telling a series of other patients (including one A. Fortiori) to 'Screw', culminating in Yossarian's run-in with Nurse Cramer - but there's a deeper purpose to the pratfalls and general grotesquerie, for it all highlights the pointlessness of war and bureaucracy (witness the inescapable influence of Wintergreen's low level malevolence, say).

There are quite a lot of loose ends - to name just a few, Doc Daneeka is left to languish as a dead man without there being any particular resolution of his fate, General Dreedle just disappears from the scene once he's replaced by General Peckem, nothing ever really happens in relation to Major --- de Coverley (though that last may be apt in terms of the figure's general inscrutability), and does Chief White Halfoat end up dying or not? - but perhaps that's apt...the narrative cycles and repeats itself, but this endless circularity ('Catch-22'!) needn't - and, in Heller's universe, doesn't - imply resolution or completion. Events are oriented around the logic of the titular 'Catch-22', which encapsulates the absurdity of it all, appearing and ramifying in guises and situations which are ever-changing but somehow always the same.

It's striking, too, that in some ways the novel evinces quite a conventional progression - the characters are introduced, we begin to sympathise with them (with figures like Yossarian and the Chaplain in particular, who eventually prove to be the (anti-)heroes of the book), and then, in order to make the author's point, they begin dying (Cathcart, Korn, Milo, and others of their ilk are, of course, insulated from any such risk, but the McWatts and Natelys begin falling with an indecent haste in the final sections of the book). They're not really grotesque characters, but they find themselves in grotesque situations (eg, war) - that reminds me of Pynchon's aphorism about paranoids (in Gravity's Rainbow?) which, paraphrased, goes something like 'paranoids are paranoids not because they're paranoid, but because they, fucking idiots, keep putting themselves in paranoid situations', but then one never really sympathises with Pynchon's characters, only identifies with the pathos of their Situations.

Catch-22 does remind me of Pynchon, and also of Dr Strangelove - these are easy comparisons, but none the less revealing for that ease, I don't think. But to me it seems to have more of a centre - a core - than Pynchon's work (not least in the forms of subjectivity and thematic development it evinces, and in its close, specific targeting of the effects of war) and more of a wildness, an unhingedness which is perhaps the prerogative of literature (as opposed to film), than Strangelove. Easy to read, but there's plenty going on.

Thursday, November 24, 2005

Hilary and Jackie

An emotionally involving film, this - I spent nearly the whole time with my arms wrapped around myself or with one hand pressed to my forehead in a kind of warding-off gesture, and realised at a couple of points that I had almost forgotten to breathe. Sometimes films take me like that, and I think that it mainly has to do with my sympathising with the characters - I squirm and wince and feel awkward and embarrassed for them...it's a very immediate experience, and I don't think it depends at all on being able to imagine myself in their shoes - just the depiction itself is enough.

Actually, the last film which provoked this sort of response in me was Punch-Drunk Love, and it may not be entirely coincidental that Emily Watson was also in that one; she's an astonishingly good actor, and I can still vividly recall how much of a punch in the guts Breaking The Waves - the first thing I saw her in - was when I watched it years ago (much as I loved it, I haven't been able to bear the thought of watching the film since). In Hilary and Jackie, as Jacqueline du Pré, she's utterly compelling - you can't take your eyes off her, and yet some of her scenes are almost unbearable to watch because of the awkwardness and rawness of her character. And Rachel Griffiths is just as good, as her sister, Hilary - in every way, she's just exactly right...both ring completely true.

This film could easily have been boring (because it's so unassuming in its conception) or tritely melodramatic (because the feelings and relationships are so deeply felt and sometimes extravagantly expressed), but both performances and screenplay are perfectly pitched and so instead it's simply lovely...one of those films that, in its modest, poignant way, is about nothing more nor less than what it is to be human and alive.

Actually, the last film which provoked this sort of response in me was Punch-Drunk Love, and it may not be entirely coincidental that Emily Watson was also in that one; she's an astonishingly good actor, and I can still vividly recall how much of a punch in the guts Breaking The Waves - the first thing I saw her in - was when I watched it years ago (much as I loved it, I haven't been able to bear the thought of watching the film since). In Hilary and Jackie, as Jacqueline du Pré, she's utterly compelling - you can't take your eyes off her, and yet some of her scenes are almost unbearable to watch because of the awkwardness and rawness of her character. And Rachel Griffiths is just as good, as her sister, Hilary - in every way, she's just exactly right...both ring completely true.

This film could easily have been boring (because it's so unassuming in its conception) or tritely melodramatic (because the feelings and relationships are so deeply felt and sometimes extravagantly expressed), but both performances and screenplay are perfectly pitched and so instead it's simply lovely...one of those films that, in its modest, poignant way, is about nothing more nor less than what it is to be human and alive.

Wednesday, November 23, 2005

The Thackery T. Lambshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric & Discredited Diseases edited by Jeff Vandermeer and Mark Roberts

Okay, squeamish isn't quite the right word, but I can be a...uh...call it 'physically sensitive' reader. A good example of this was the fashion in which, when I was reading Anne Rice's Interview with the Vampire series, back in the day, I often noticed that a large vein at the side of my throat would start throbbing in sympathy after a while - I don't know if it was actually the jugular, but even if it wasn't, quite possibly all that matters is that I thought that it was. And reading descriptions of throats being cut or wrists slit often make me physically uncomfortable to the point that I have to stop reading for a while and think hard about something else (the description of the murder early in Kate Atkinson's latest, Case Histories, had that effect on me).

For that reason, I found that I wasn't able to read too much of this Pocket Guide at any one sitting. See, it's ostensibly a medical guide to, as its title suggests, a variety of diseases which fall somewhat beyond the compass of orthodox diagnosis. Its major part is comprised of individual entries for particular diseases (submitted by a long roll call of worthies including Miéville, Moorcock, Gaiman and Alan Moore), ranging from: Ballistic Organ Syndrome, which: "manifests as a sudden, explosive discharge of one or more bodily organs at high velocity; this exit may be accompanied by some pain"; to Inverted Drowning Syndrome; to Mongolian Death Worm Infestation, to Postal Carriers' Brain Fluke Syndrome, propagated by flukes whose mode of dissemination is so elaborate and dependent on fortuities that they seem to be "performing an extinction-defying trapeze act purely for the sake of impressing other parasites" (with accompanying footnote to a book entitled Vanity: Watch Spring of Evolution); to Reverse Pinocchio Syndrome, in which people who tell a great number of lies are eventually afflicted by the development of a black hole in one nostril once it has developed its own gravity, eventually resulting in the skull being sucked into the black hole itself. Scores of them, each detailed in terms of symptoms, first known case, treatment and cures, etc. Gross, and funny.

Also includes a publishing history of the Pocket Guide (this is supposedly the 83rd edition) complete with reproductions of covers and entries from past editions, an 'obscure medical history of the twentieth century', in which phenomena including but far from limited to the career and demise of Freud, Stalingrad, the Kennedy assassination, and AIDS are explained in terms of the diseases enumerated, various reminiscences written by other doctors who have encountered the formidable Lambshead in the course of his storied career, an introduction by the centenarian Lambshead himself, and various other odds and ends, including 'a disease guide benediction for the health & safety of all contributors, readers, and (sympathetic) reviewers', which concludes (and this made me laugh out loud - too much philosophy for me lately, obviously):

So obviously all of this is made up, from the diseases themselves to the spurious biography and historiography of Lambshead and the Guide. On one level, it satirises the pretension of medical guides and the language and style in which they're written. But that's really just a launching-pad for some very postmodern imaginative pyrotechnics, as many of the disease entries are written by authors who've apparently been infected by the diseases themselves, other of the diseases can be transmitted by being read about, and self-referentiality, inter-textuality (Borges - a natural touchstone for this kind of speculative writing - is mentioned as often as made-up legends of the eccentric disease field), and so on. Definitely recommendable, though some might find its general attitude of too-clever-for-its-own-goodness to be a bit annoying.

Some information here.

For that reason, I found that I wasn't able to read too much of this Pocket Guide at any one sitting. See, it's ostensibly a medical guide to, as its title suggests, a variety of diseases which fall somewhat beyond the compass of orthodox diagnosis. Its major part is comprised of individual entries for particular diseases (submitted by a long roll call of worthies including Miéville, Moorcock, Gaiman and Alan Moore), ranging from: Ballistic Organ Syndrome, which: "manifests as a sudden, explosive discharge of one or more bodily organs at high velocity; this exit may be accompanied by some pain"; to Inverted Drowning Syndrome; to Mongolian Death Worm Infestation, to Postal Carriers' Brain Fluke Syndrome, propagated by flukes whose mode of dissemination is so elaborate and dependent on fortuities that they seem to be "performing an extinction-defying trapeze act purely for the sake of impressing other parasites" (with accompanying footnote to a book entitled Vanity: Watch Spring of Evolution); to Reverse Pinocchio Syndrome, in which people who tell a great number of lies are eventually afflicted by the development of a black hole in one nostril once it has developed its own gravity, eventually resulting in the skull being sucked into the black hole itself. Scores of them, each detailed in terms of symptoms, first known case, treatment and cures, etc. Gross, and funny.

Also includes a publishing history of the Pocket Guide (this is supposedly the 83rd edition) complete with reproductions of covers and entries from past editions, an 'obscure medical history of the twentieth century', in which phenomena including but far from limited to the career and demise of Freud, Stalingrad, the Kennedy assassination, and AIDS are explained in terms of the diseases enumerated, various reminiscences written by other doctors who have encountered the formidable Lambshead in the course of his storied career, an introduction by the centenarian Lambshead himself, and various other odds and ends, including 'a disease guide benediction for the health & safety of all contributors, readers, and (sympathetic) reviewers', which concludes (and this made me laugh out loud - too much philosophy for me lately, obviously):

Z is for Zeno's paradoxysm, which fills us with misgiving,

By infinitely tiny steps it deadens but won't kill.

As no one could be sure if Aunt Augusta was still living

We propped her in her favorite chair to wait. She's waiting still.

So obviously all of this is made up, from the diseases themselves to the spurious biography and historiography of Lambshead and the Guide. On one level, it satirises the pretension of medical guides and the language and style in which they're written. But that's really just a launching-pad for some very postmodern imaginative pyrotechnics, as many of the disease entries are written by authors who've apparently been infected by the diseases themselves, other of the diseases can be transmitted by being read about, and self-referentiality, inter-textuality (Borges - a natural touchstone for this kind of speculative writing - is mentioned as often as made-up legends of the eccentric disease field), and so on. Definitely recommendable, though some might find its general attitude of too-clever-for-its-own-goodness to be a bit annoying.

Some information here.

Van Helsing

Gosh, this is a really bad movie. It has precisely two redeeming features: great set design, and comic relief from David Wenham. Apart from that, unremittingly awful - basically boring and frequently so bad it's laughable. Two hours of my life that would've been much better spent wrapped up in books.

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

The Cardigans - First Band on the Moon

Cool Scandinavian indie-pop with a bit of an edge, circa '96. This is the one with "Lovefool" (not to mention a Black Sabbath cover). "Lovefool" still a joy after all these years and despite constant listening on R+J soundtrack, "Great Divide" nice in a chimey fairground "Mike Mills" (as in the Air song) kind of way, and a couple of others deliciously off-kilter and catchy, though most of the songs on this record can't hold a candle to the band's simply splendid (and splendidly titled) current single, "I Need Some Fine Wine And You, You Need To Be Nicer".

Another list: Key early books

And while I'm excavating my past as a reader, here's my attempt at recalling and listing the books which left a deep impression when I read them in primary school (no doubt I'll miss many, but anyway...):

- The Green Wind by Thurley Fowler. This just might have been the first 'proper' book that I really loved and treasured. Looking back, it's easy to see why I was drawn to the central character, Jennifer - a sarcastic, prickly, but sympathetically-rendered 11yo type with aspirations of being a writer who feels herself to be different from everyone else - but at the time, all I knew was that the book spoke to me. Years later, I was pleasantly surprised when I learnt that Penny, one of my best friends from uni, had felt similarly about the book at the corresponding time in her life - indeed, being female and approximately red-haired, and having grown up in the country, she's much more of a Jennifer type than I.

- Master of the Grove by Victor Kelleher. Might well have been the book which first opened my eyes to the wonder that literature can bring.

- Space Demons by Gillian Rubenstein. This one just caught my imagination and wouldn't let go. I dreamt about it - and its sequel, Skymaze, too.

- Gone With The Wind by Margaret Mitchell. Pulled my mum's tatty old copy from the book shelf one woozy summer day and lost the next few weeks to its reading, completely wrapped up in its drowsy charms; have re-read several times since (most recently a couple of years back - I wrote about it on open diary at the time), finding it to be almost a completely different and new book each time.

- To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee. I'm not 100% sure, but I think that this was the book which first planted the thought that I might want to be a lawyer. It really stirred me up when I read it, even though I'm sure that I didn't grasp half of what was going on. For some reason it came up in a scholarship interview I went to in grade 6 (for year 7 onwards) at Melbourne Grammar, and I remember the headmaster asking what I thought about capital punishment...heavens know what I answered!

- Small Gods by Terry Pratchett. The first Pratchett book I read and, for better or for worse (I'm much inclined to think 'better'), the beginning of a very long and deep engagement indeed.

I suspect there were at least one or two others, but those are the ones which spring to mind right now.

- The Green Wind by Thurley Fowler. This just might have been the first 'proper' book that I really loved and treasured. Looking back, it's easy to see why I was drawn to the central character, Jennifer - a sarcastic, prickly, but sympathetically-rendered 11yo type with aspirations of being a writer who feels herself to be different from everyone else - but at the time, all I knew was that the book spoke to me. Years later, I was pleasantly surprised when I learnt that Penny, one of my best friends from uni, had felt similarly about the book at the corresponding time in her life - indeed, being female and approximately red-haired, and having grown up in the country, she's much more of a Jennifer type than I.

- Master of the Grove by Victor Kelleher. Might well have been the book which first opened my eyes to the wonder that literature can bring.

- Space Demons by Gillian Rubenstein. This one just caught my imagination and wouldn't let go. I dreamt about it - and its sequel, Skymaze, too.

- Gone With The Wind by Margaret Mitchell. Pulled my mum's tatty old copy from the book shelf one woozy summer day and lost the next few weeks to its reading, completely wrapped up in its drowsy charms; have re-read several times since (most recently a couple of years back - I wrote about it on open diary at the time), finding it to be almost a completely different and new book each time.

- To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee. I'm not 100% sure, but I think that this was the book which first planted the thought that I might want to be a lawyer. It really stirred me up when I read it, even though I'm sure that I didn't grasp half of what was going on. For some reason it came up in a scholarship interview I went to in grade 6 (for year 7 onwards) at Melbourne Grammar, and I remember the headmaster asking what I thought about capital punishment...heavens know what I answered!

- Small Gods by Terry Pratchett. The first Pratchett book I read and, for better or for worse (I'm much inclined to think 'better'), the beginning of a very long and deep engagement indeed.

I suspect there were at least one or two others, but those are the ones which spring to mind right now.

George R R Martin - A Game of Thrones, A Clash of Kings & A Storm of Swords

Having drugged myself into a familiar, dazed drowsiness with these three hefty volumes for the better part of the time since that last paper was handed in, I've been wondering just why I read (and re-read) fantasy. The genre was pretty significant in the development of my reading habits - I remember Victor Kelleher's Master of the Grove making a huge impression at some point which must've been no later than grade 4, since I have a distinct memory of reading it in the library of my old primary school, and at around that time there were also those godawful 'choose your own adventure'-type books (I can't remember the series title, but they had bright green covers and were written by Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone [sp?])...and then, I think, it was David Eddings (and Terry Pratchett) from grade 6 and Stephen Donaldson the year after, in AAP (again, distinct memory of reading and being amazed by Lord Foul's Bane on the way up to camp). I'm pretty sure that Eddings was the first author whose books I was reading from the 'adult' (as opposed to 'junior'/'teenage') section of the library...somewhere in those early years I also read Tolkien and was suitably awed.

At the time, and even (especially?) through high school, I loved the genre because it was so epic - it held the promise of richer, more magical worlds, and, at its best, had such heft and sweep, and my teenage years were stormy and black enough (or, at least, so they seemed at the time, which is of course what counts) that the sheer escapism must've been alluring (though I don't think I ever thought of it in quite those terms). It's really hard to articulate, and I don't think I could've done so properly even at the time when I really felt it.

The thing is, though, that I don't feel it any more, not really, which brings me back to where I started: why do I read these books? I guess that in part it's indolence - they're so easy to read, and an enjoyable escape (even if they no longer make my spine tingle, or at least not as much as they used to), and if I'm going to read anyway, why not? Not really a very good answer, but maybe it wasn't a very good question in the first place.

As to the "Song of Ice and Fire" series itself: Well, this one I only read last year (well, read up to its current state, anyway - it's not yet finished by the author), I think, or the year before at the very earliest, and it struck me at the time as one of the best epic fantasy series out there. Simply put, it's gripping. It has gravitas and the all-important epic sweep, but it also has well-drawn, interesting characters. There's political intrigue a-plenty - much moving of pieces around the board (fates of nations and individual consciences both at stake), unexpected reversals of luck and loyalty, marriages promised and broken for the sake of alliances...the great families bound to one another by a complex merry-go-round of arranged marriages, children of enemies warded in foreign lands, imprisonments, ransoms, escapes, recaptures, characters flung together in strange configurations as they jostle and are jostled for position. But the battle and action scenes are also well done, and Martin doesn't stint on the characterisation either (witness Catelyn's complex emotions, or Tyrion, or the arc followed by Jaime Lannister, to name just a few), nor on the surprises (the first time I read these books, I was astonished when Eddard Stark died, and again when Robb met the same fate). Nor does he go overboard with the magical or fantastic elements - they become gradually more prominent as the series goes on. One of the glowing comments on the back of the books references the War of the Roses, and I reckon that's exactly right. On this re-read, it's slightly less excellent (unsurprisingly) but still pretty darn good.

At the time, and even (especially?) through high school, I loved the genre because it was so epic - it held the promise of richer, more magical worlds, and, at its best, had such heft and sweep, and my teenage years were stormy and black enough (or, at least, so they seemed at the time, which is of course what counts) that the sheer escapism must've been alluring (though I don't think I ever thought of it in quite those terms). It's really hard to articulate, and I don't think I could've done so properly even at the time when I really felt it.

The thing is, though, that I don't feel it any more, not really, which brings me back to where I started: why do I read these books? I guess that in part it's indolence - they're so easy to read, and an enjoyable escape (even if they no longer make my spine tingle, or at least not as much as they used to), and if I'm going to read anyway, why not? Not really a very good answer, but maybe it wasn't a very good question in the first place.

As to the "Song of Ice and Fire" series itself: Well, this one I only read last year (well, read up to its current state, anyway - it's not yet finished by the author), I think, or the year before at the very earliest, and it struck me at the time as one of the best epic fantasy series out there. Simply put, it's gripping. It has gravitas and the all-important epic sweep, but it also has well-drawn, interesting characters. There's political intrigue a-plenty - much moving of pieces around the board (fates of nations and individual consciences both at stake), unexpected reversals of luck and loyalty, marriages promised and broken for the sake of alliances...the great families bound to one another by a complex merry-go-round of arranged marriages, children of enemies warded in foreign lands, imprisonments, ransoms, escapes, recaptures, characters flung together in strange configurations as they jostle and are jostled for position. But the battle and action scenes are also well done, and Martin doesn't stint on the characterisation either (witness Catelyn's complex emotions, or Tyrion, or the arc followed by Jaime Lannister, to name just a few), nor on the surprises (the first time I read these books, I was astonished when Eddard Stark died, and again when Robb met the same fate). Nor does he go overboard with the magical or fantastic elements - they become gradually more prominent as the series goes on. One of the glowing comments on the back of the books references the War of the Roses, and I reckon that's exactly right. On this re-read, it's slightly less excellent (unsurprisingly) but still pretty darn good.

Alison Lurie - Love & Friendship

I can be a boy of obscure whims; one such, of a little while ago, was the desire to be complimented on some item of my wardrobe (it didn't really matter much which item) so that I'd be able to reply, 'Oh, this old thing?'.

As I said, obscure.

Anyhow, this book reminded me of that passing thought, for its characters - middle-upper class university academics and their wives in a secluded New England university town, some time in the 1950s (as far as I could gather) - are just the sorts to utter such words. Take this passage, for example:

Or this one:

One interesting thing about Lurie's writing - apparent in that first passage - is that she writes, self-consciously or otherwise, in much the same voice as that adopted by her characters ('but she did not care for it'). In part, this is because the narrative voice is almost exclusively that of one or the other of the characters (that is, it's presented as the thoughts of one of the characters - in conventional third person prose, though, rather than Joycean stream of consciousness), sometimes in the form of letters. There's an amusing little digression in there somewhere in which Holman reflects that Emmy's use of intensifiers ('perfectly horrid', 'terribly thoughtful', etc) actually indicates a diminution of feeling/opinion - I wonder whether that's an entirely fair appraisal, though (not that Lurie necessarily endorses Holton's p.o.v., etc, etc). Much use made of adverbs in general, sometimes as qualifiers ('rather delightful'). (These examples aren't actually from the book itself, but they might as well be.)

So, the milieu is academia (university lecturers and administrators; not students except at the margins) in a very particular time and place, mostly the humanities - not a microcosm for the rest of the world because, as one of the characters notes, all of the violence and irrationality has been abstracted (besides, most of the world doesn't make passing references to Keats, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Hobbes, classical mythology, Arthur Conan Doyle, Somerset Maugham, and so on in casual conversation), but still a fascinating study, at least for me.

Focuses on the little intrigues and maneuvers (both academic and personal), and the petty and major disasters (again, across both dimensions) of the town's inhabitants, tracking them through dinner parties, faculty meetings, clandestine encounters in parks, chance run-ins at supermarkets. Social dynamics strongly determined by class and other traditional indicia of social status, filtered through and inseparable from the university hierarchy. Cast of nouveau riches, frightfully well-bred old money types, 'picturesque' (Lurie's description not mine, and a good one) arty semi-bohemian types, drifting musicians, struggling young instructors, boorish/feared senior professors, inept and mildly corrupt administrators, and their wives (who are very much active subjects in their own right) and children. Much time spent on the merits and otherwise of the divisive 'Humanities C' course. In some faint way, put me in mind of The Great Gatsby. Often very amusing, albeit more in a 'wry smile' than 'laugh out loud' way.

All of which should be more than enough to explain why I like this book so much.

* * *

As I said, obscure.

Anyhow, this book reminded me of that passing thought, for its characters - middle-upper class university academics and their wives in a secluded New England university town, some time in the 1950s (as far as I could gather) - are just the sorts to utter such words. Take this passage, for example:

Feeling rebuked, Emmy removed herself. This time she went upstairs and began to straighten out Freddy's closet. All I have to do to keep Mrs Rabbage quiet is to insult her now and then, Emmy thought to herself, and she gave the kind of cheerful laugh that might be supposed to go with this kind of cheer, but she did not care for it. She was chagrined to think that she had spoken rudely to a servant.

Or this one:

'Hateful thing,' Miranda said, kicking the stove. 'And do you know, when we first moved in here I was completely enchanted with it. Oh, lord!' She snatched the coffee-pot up just as it boiled over. 'I'm so sorry. That just shows you. Do you still want some?'

One interesting thing about Lurie's writing - apparent in that first passage - is that she writes, self-consciously or otherwise, in much the same voice as that adopted by her characters ('but she did not care for it'). In part, this is because the narrative voice is almost exclusively that of one or the other of the characters (that is, it's presented as the thoughts of one of the characters - in conventional third person prose, though, rather than Joycean stream of consciousness), sometimes in the form of letters. There's an amusing little digression in there somewhere in which Holman reflects that Emmy's use of intensifiers ('perfectly horrid', 'terribly thoughtful', etc) actually indicates a diminution of feeling/opinion - I wonder whether that's an entirely fair appraisal, though (not that Lurie necessarily endorses Holton's p.o.v., etc, etc). Much use made of adverbs in general, sometimes as qualifiers ('rather delightful'). (These examples aren't actually from the book itself, but they might as well be.)

So, the milieu is academia (university lecturers and administrators; not students except at the margins) in a very particular time and place, mostly the humanities - not a microcosm for the rest of the world because, as one of the characters notes, all of the violence and irrationality has been abstracted (besides, most of the world doesn't make passing references to Keats, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Hobbes, classical mythology, Arthur Conan Doyle, Somerset Maugham, and so on in casual conversation), but still a fascinating study, at least for me.

Focuses on the little intrigues and maneuvers (both academic and personal), and the petty and major disasters (again, across both dimensions) of the town's inhabitants, tracking them through dinner parties, faculty meetings, clandestine encounters in parks, chance run-ins at supermarkets. Social dynamics strongly determined by class and other traditional indicia of social status, filtered through and inseparable from the university hierarchy. Cast of nouveau riches, frightfully well-bred old money types, 'picturesque' (Lurie's description not mine, and a good one) arty semi-bohemian types, drifting musicians, struggling young instructors, boorish/feared senior professors, inept and mildly corrupt administrators, and their wives (who are very much active subjects in their own right) and children. Much time spent on the merits and otherwise of the divisive 'Humanities C' course. In some faint way, put me in mind of The Great Gatsby. Often very amusing, albeit more in a 'wry smile' than 'laugh out loud' way.

All of which should be more than enough to explain why I like this book so much.

* * *

Something was wrong with the game, though. 'But they're all blindfolded!' Emmy objected.

'Yes,' Miranda said. 'They like it better that way.'

Monday, November 21, 2005

Alison Krauss + Union Station - New Favorite

All the accoutrements of this elegant modern bluegrass-styled music - most notably, Krauss's voice - taken together make for a really nice sound, guitar and Dobro more prominent than banjo, fiddle or mandolin. There's a pleasant airiness to proceedings (especially on songs like "The Lucky One" and "New Favorite", not coincidentally two which I already knew), with neither the 'mountain' nor 'melancholy' (obviously not opposed to each other) aspects of these stylings pushed too strongly, and the record hangs together well. Still, I haven't yet taken this one to heart - maybe that'll come with time, or maybe it's a function of my approaching it from the pop end of the spectrum rather than the bluegrass/folk. That said, I'm writing this after less than a day of repeat playing, and have probably spun it about a half dozen times already, liking it a tiny bit more each time, so who knows?

Minutiae: (1) Amusingly, I found it in the 'jazz' section at the library (and labelled as such); and (2) the title track was written by Gillian Welch and David Rawlings.

Minutiae: (1) Amusingly, I found it in the 'jazz' section at the library (and labelled as such); and (2) the title track was written by Gillian Welch and David Rawlings.

War of the Worlds

Of all the early sci-fi/adventure novels by Verne, Wells and co, a large number of which I seem to've read somewhere along the line between primary school and now, The War of the Worlds has always stood out, even though my memory of it is fairly vague. I saw one of the 1950s versions on video when quite young (I think there was a whole series, and I happened to watch the first one) and it left a strong impression - it was frightening. The book also left me quite uneasy, in part because of what I recall as being its somewhat distanced, clinical air of reportage (though I presumably didn't think about it in quite those terms back then). And I also knew the story of the whole Orson Welles radio broadcast thing, which added to the intrigue surrounding the book.

So, when I came to watch this adaptation, I considered it auspicious when the introductory prologue (after the pull-back shot from microsopic view to universe) consisted of an old-fashioned montage and reassuringly sonorous male 'historical' voiceover. The film proper gets off to a good start, too - I didn't mind that it focused on Tom Cruise and his family, rather than depicting Pentagon generals or fighter pilots or their ilk...in fact, this seemed a good approach given that, in the end, it's the air itself which brings the invaders undone rather than any technological might or scientific nous on humanity's part (though Spielberg can't resist giving us the sight of the military shooting down one of the tripods after its shields fail, complete with suitably vanquished - ie, dead ('the only good alien's a dead alien!'; wrong movie, I know...) - alien emerging at the end).

The scenes of destruction get the job done, and there's a pervasive unsettling feeling to much of the film (eg, the ghostly shots of the family's faces early on, the menacing fellow who takes Ray and Rachel into his basement, and particularly the culmination of that encounter), which is suitable. But the character arcs are predictable and not entirely convincing, and with the focus on the individuals and not on larger-than-life heroes, that proves to be a telling flaw. As a film crit might say, three stars out of five.

So, when I came to watch this adaptation, I considered it auspicious when the introductory prologue (after the pull-back shot from microsopic view to universe) consisted of an old-fashioned montage and reassuringly sonorous male 'historical' voiceover. The film proper gets off to a good start, too - I didn't mind that it focused on Tom Cruise and his family, rather than depicting Pentagon generals or fighter pilots or their ilk...in fact, this seemed a good approach given that, in the end, it's the air itself which brings the invaders undone rather than any technological might or scientific nous on humanity's part (though Spielberg can't resist giving us the sight of the military shooting down one of the tripods after its shields fail, complete with suitably vanquished - ie, dead ('the only good alien's a dead alien!'; wrong movie, I know...) - alien emerging at the end).

The scenes of destruction get the job done, and there's a pervasive unsettling feeling to much of the film (eg, the ghostly shots of the family's faces early on, the menacing fellow who takes Ray and Rachel into his basement, and particularly the culmination of that encounter), which is suitable. But the character arcs are predictable and not entirely convincing, and with the focus on the individuals and not on larger-than-life heroes, that proves to be a telling flaw. As a film crit might say, three stars out of five.

Saturday, November 19, 2005

Neil Young with Crazy Horse - Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere

Well, the three famous songs - "Cinnamon Girl", "Down By The River" and "Cowgirl In The Sand" - are the three most memorable, and together comprise more than half of the running time of Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. As to the others, the title track is one of those jangly mid-tempo semi-rockers that Neil does well, and is indeed quite good, "Round & Round (It Won't Be Long)" is a slow, not unpleasant but basically forgettable tune, "The Losing End (When You're On)" comes back to the mid-tempoisms, and "Running Dry (Requiem For The Rockets)" comes across as a kind of drunken dirge (it could be the strings).

As that summation suggests, this record is, for me, one of two parts - the three songs I knew, and then the rest. In fact, those three basically orient the album, which is bookended by "Cinnamon Girl" and "Cowgirl In The Sand" and seems to cohere around "Down By The River" at its centre. So, while I suppose that it must be good, it's hard for me to listen to it as a whole because, depending on how I'm listening to it on the particular occasion, either the famous ones or the ones I hadn't heard before tend to 'bulge' out as a group.

As that summation suggests, this record is, for me, one of two parts - the three songs I knew, and then the rest. In fact, those three basically orient the album, which is bookended by "Cinnamon Girl" and "Cowgirl In The Sand" and seems to cohere around "Down By The River" at its centre. So, while I suppose that it must be good, it's hard for me to listen to it as a whole because, depending on how I'm listening to it on the particular occasion, either the famous ones or the ones I hadn't heard before tend to 'bulge' out as a group.

Hem - Eveningland

Gentle, sighing, soughing folk music. The singer (Sally Ellyson) has one of those heart in her throat type voices, and the full range of instrumentation that one would expect is around it - twangy and acoustic guitars, mandolin, banjo, piano, strings, assorted percussion and orchestral effects - and it's all very sweet and nice. It's kind of end-of-day music ('eveningland', I suppose) - graceful, delicate and finely-wrought - but with more of a tendency towards highlighted, upswooping choruses and occasional baroque ornateness than I'd expected, sometimes pulling the songs more towards the melancholy, downbeat end of country than the folk streams in which they're rooted.

It's very sincere, and more trad than, say, Azure Ray (and neither better nor worse than that duo by virtue of it - just different)...and is on Rounder rather than Saddle Creek, which pretty much tells the story. It's a bit strange listening to it, though, and reflecting that it must be closer to the origins of this kind of music than those who've become more popular with variations on it, but hearing bits of outfits like Azure Ray (not that they've yet become immensely popular), Mojave 3, the Sundays, even up-to-and-including-Surfacing Sarah McLachlan (especially, in relation to that last, on "Redwing"). I prefer the more mournful-sounding numbers - "Pacific Street", which I'd heard before, is my favourite.

It's very sincere, and more trad than, say, Azure Ray (and neither better nor worse than that duo by virtue of it - just different)...and is on Rounder rather than Saddle Creek, which pretty much tells the story. It's a bit strange listening to it, though, and reflecting that it must be closer to the origins of this kind of music than those who've become more popular with variations on it, but hearing bits of outfits like Azure Ray (not that they've yet become immensely popular), Mojave 3, the Sundays, even up-to-and-including-Surfacing Sarah McLachlan (especially, in relation to that last, on "Redwing"). I prefer the more mournful-sounding numbers - "Pacific Street", which I'd heard before, is my favourite.

Pure Movies

It was seeing Björk's name on the front which caused me to pick this up, and not recognising the song's title, "Play Dead", which caused me to buy it, coupled with the roll call of famous film songs that it contains (every last one of which I'd heard before - including, it turns out, the Björk cut...but I'm pretty sure that I don't have it on cd anywhere else, and it's a good song, suitably dramatic). The flavour of the thing can be appreciated by way of some thoughts about a few of the songs:

- "Love Is All Around". The first song on the compilation - enough said, really. Others in the 'enough said' category: "How Deep Is Your Love", "Up Where We Belong", "Lady In Red", "Unchained Melody", "I Just Called To Say I Love You", etc, etc.

- "Stuck In The Middle With You". This song has reminded me of Dylan in the past.

- "Blaze Of Glory". Some days I'm sorry that I taped over that old Bon Jovi best of. I mean, I probably replaced it with some Pink Floyd album or other...seriously, which one would I more often want to listen to? Bon Jovi'd win hands down.

- "I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do". And all the Concretes, Shangri-Las, etc must be having an effect, 'cause I've been quite enjoying this one. So this is what they mean what they talk about slippery slopes...

- "Nights In White Satin". Well, next time I feel like listening to this song (ie, come next blue moon), I'll be able to do so on cd instead of firing up the groaning old laptop, I guess. Here, it's the triumphant set closer.

Bonus! There's an East 17 song! Wow, that Kalifornia soundtrack must be pretty weird.

- "Love Is All Around". The first song on the compilation - enough said, really. Others in the 'enough said' category: "How Deep Is Your Love", "Up Where We Belong", "Lady In Red", "Unchained Melody", "I Just Called To Say I Love You", etc, etc.

- "Stuck In The Middle With You". This song has reminded me of Dylan in the past.

- "Blaze Of Glory". Some days I'm sorry that I taped over that old Bon Jovi best of. I mean, I probably replaced it with some Pink Floyd album or other...seriously, which one would I more often want to listen to? Bon Jovi'd win hands down.

- "I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do". And all the Concretes, Shangri-Las, etc must be having an effect, 'cause I've been quite enjoying this one. So this is what they mean what they talk about slippery slopes...

- "Nights In White Satin". Well, next time I feel like listening to this song (ie, come next blue moon), I'll be able to do so on cd instead of firing up the groaning old laptop, I guess. Here, it's the triumphant set closer.

Bonus! There's an East 17 song! Wow, that Kalifornia soundtrack must be pretty weird.

Tim Winton - The Turning

Well, the best way to describe this collection of linked short stories would have to be 'Wintonesque' - they're so recognisably written in his voice, and set in the small town Australian milieu which he's made his own. It'd be easy to dismiss his imagery and symbolism as heavy-handed and obvious - 'literature for people who don't read literature' is the slur I might sling, if I were minded to do so - but, when Winton's name comes up (as it often does), I more often find myself arguing the opposite. I feel that his writing is very honest - unadorned without being plain...it's as if he, as a writer, is producing these books and saying 'well, this is what my writing is - take it or leave it', without any attempts to distract or cozen the reader. But simplicity is not always lack of subtlety or craft.

The Turning, then. More bruised, battling types, trying to make a go of things, poised between failure and contingent success (which only ever, in this world, seems to mean 'survival'). It's delicately done, though - the characters emerge and re-emerge as they cycle through the stories in different guises and are seen from different perspectives, and different parts of their individual and collective histories come to light. I'm not intimately familiar with his previous work, but I got the sense that these were maybe a bit less mysterious, less touched by grace, less filled by those minor key redemptive (or maybe 'affirmatory') moments. Good, though - I sat up nearly all night to finish it.

The Turning, then. More bruised, battling types, trying to make a go of things, poised between failure and contingent success (which only ever, in this world, seems to mean 'survival'). It's delicately done, though - the characters emerge and re-emerge as they cycle through the stories in different guises and are seen from different perspectives, and different parts of their individual and collective histories come to light. I'm not intimately familiar with his previous work, but I got the sense that these were maybe a bit less mysterious, less touched by grace, less filled by those minor key redemptive (or maybe 'affirmatory') moments. Good, though - I sat up nearly all night to finish it.

Wednesday, November 16, 2005

The axe for the frozen sea inside us: Summer reading list

Well, university is all over bar the handing-in tomorrow, so I thought that I'd make a partial summer reading list, composed indiscriminately of books that people have given me, books which I've bought but not read, books on one of my various lists of 'books to read' lists (some based on recommendations, some because I came across them while doing research for my literature essays, and some for no reason that I can recall), new and forthcoming books by favourite authors, books which I've been meaning to re-read, and academic books which I don't seriously think I'm actually going to get through. In no particular order:

Günter Grass - The Flounder

Nikolai Gogol - Dead Souls

Alasdair Gray - A History Maker

Joseph Heller - Catch 22

Kazuo Ishiguro - The Remains Of The Day

Vladimir Nabokov - Pale Fire

Tim Winton - The Turning

Marcel Proust - Swann's Way

Raymond Queneau - The Bark Tree

Italo Calvino - If On A Winter's Night A Traveler

Thomas Pynchon - Mason & Dixon

Ian Watson - Chekhov's Journey

A S Byatt - Possession

Aragon - La Mise à Mort

Gérard de Nerval - Aurélia

Louis Guilloux - Le Sang Noir

Amélie Nothomb - Antechrista

China Miéville - Looking For Jake

Terry Pratchett - Thud

George R R Martin - A Feast For Crows [though I'll probably have to go back and read the earlier ones first, to refresh my memory]

Zadie Smith - On Beauty

Jacques Derrida - Of Grammatology

Edmund Husserl - Ideas

Also, a couple of names: Alison Lurie and Ivy Compton-Burnett.

Anyway, obviously I won't read all of those (and, conversely, will read many not on the list), but I can't help but feel that the making of a list like this is an optimistic gesture, in ways which extend beyond just reading and literature.

Günter Grass - The Flounder

Nikolai Gogol - Dead Souls

Alasdair Gray - A History Maker

Joseph Heller - Catch 22

Kazuo Ishiguro - The Remains Of The Day

Vladimir Nabokov - Pale Fire

Tim Winton - The Turning

Marcel Proust - Swann's Way

Raymond Queneau - The Bark Tree

Italo Calvino - If On A Winter's Night A Traveler

Thomas Pynchon - Mason & Dixon

Ian Watson - Chekhov's Journey

A S Byatt - Possession

Aragon - La Mise à Mort

Gérard de Nerval - Aurélia

Louis Guilloux - Le Sang Noir

Amélie Nothomb - Antechrista

China Miéville - Looking For Jake

Terry Pratchett - Thud

George R R Martin - A Feast For Crows [though I'll probably have to go back and read the earlier ones first, to refresh my memory]

Zadie Smith - On Beauty

Jacques Derrida - Of Grammatology

Edmund Husserl - Ideas

Also, a couple of names: Alison Lurie and Ivy Compton-Burnett.

Anyway, obviously I won't read all of those (and, conversely, will read many not on the list), but I can't help but feel that the making of a list like this is an optimistic gesture, in ways which extend beyond just reading and literature.

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

On perfect albums (and a list of my current top 20 favourite albums ever)

Listening to "American Flag" this afternoon and remembering why it's so great, I got to wondering about how I make sense out of my 'favourite' albums. Thinking about the lps which I do think of as my favourites, it's striking that I wouldn't consider any of them to be flawless or perfect (even to the extent that these are meaningful concepts when applied to pop records) - the closest are probably Loveless and Treasure, and in that respect it's probably telling that they're likely the two most distinctive-sounding records on the list (see below) and so perhaps the easiest to think of as 'perfect'.

Take Moon Pix, for example. I love this album, and definitely consider it to be one of my favourites, but for me, after the opening-in-glory that is "American Flag", it doesn't really properly hit its stride again until the run home, starting with track 7, "Moonshiner". So what's with that? It's one of my favourite albums and yet I reckon that it hasn't really 'hit its stride' for the better part of half its running time? Or take Funeral (admittedly an atypical one in that it's only been part of my life for a span of months, rather than years): there are really only two songs on that album - "Neighbourhood #1 (Tunnels)" and "Rebellion (Lies)" - which I out and out love (though obviously any record on which cuts like "In The Backseat", "Neighbourhood #3 (Power Out)", "Haiti", etc, can be 'second tier' has a lot going for it), and yet right now I'm definitely counting it as a 'favourite'.

Some of it may be down to how 'high' the high points are. Plus, some of us are just wired to respond to the sound of certain albums. And it's never wise to underestimate the effect of the right record coming along at the right time...

Another important part of what's going on here is that 'perfection' and 'flawlessness' must be, to some extent, relativised to the particular album. Kate B once opined that Tigermilk was a perfect album, and I pretty much agreed (and still do), at least to the extent that it's a perfect album on its own terms...and this despite my thinking that Sinister (and maybe even Arab Strap) is probably 'better'. But how does that work? There's got to be an interplay between, on the one hand, the way in which every album - like every work of art - in some sense sets its own terms, and, on the other hand, the overall framework within which we make these kinds of value judgments, right? So where does that leave us?

Well, with another variation on the old subjective/objective thing, I suppose. In other words, it's ineffable.

* * *

1. Bachelor No 2, or The Last Remains of the Dodo - Aimee Mann

2. OK Computer - Radiohead

3. Loveless - My Bloody Valentine

4. Treasure - Cocteau Twins

5. Blue Bell Knoll - Cocteau Twins

6. The Velvet Underground & Nico - The Velvet Underground & Nico

7. Moon Pix - Cat Power

8. On Fire - Galaxie 500

9. New Adventures In Hi-Fi - R.E.M.

10. Summerteeth - Wilco

11. Homogenic - Björk

12. Isn't Anything - My Bloody Valentine

13. The Queen Is Dead - The Smiths

14. The Bends - Radiohead

15. Psychocandy - The Jesus and Mary Chain

16. Closer - Joy Division

17. Funeral - The Arcade Fire

18. Disintegration - The Cure

19. f#a#∞ - Godspeed You Black Emperor!

20. Blacklisted - Neko Case

Take Moon Pix, for example. I love this album, and definitely consider it to be one of my favourites, but for me, after the opening-in-glory that is "American Flag", it doesn't really properly hit its stride again until the run home, starting with track 7, "Moonshiner". So what's with that? It's one of my favourite albums and yet I reckon that it hasn't really 'hit its stride' for the better part of half its running time? Or take Funeral (admittedly an atypical one in that it's only been part of my life for a span of months, rather than years): there are really only two songs on that album - "Neighbourhood #1 (Tunnels)" and "Rebellion (Lies)" - which I out and out love (though obviously any record on which cuts like "In The Backseat", "Neighbourhood #3 (Power Out)", "Haiti", etc, can be 'second tier' has a lot going for it), and yet right now I'm definitely counting it as a 'favourite'.

Some of it may be down to how 'high' the high points are. Plus, some of us are just wired to respond to the sound of certain albums. And it's never wise to underestimate the effect of the right record coming along at the right time...

Another important part of what's going on here is that 'perfection' and 'flawlessness' must be, to some extent, relativised to the particular album. Kate B once opined that Tigermilk was a perfect album, and I pretty much agreed (and still do), at least to the extent that it's a perfect album on its own terms...and this despite my thinking that Sinister (and maybe even Arab Strap) is probably 'better'. But how does that work? There's got to be an interplay between, on the one hand, the way in which every album - like every work of art - in some sense sets its own terms, and, on the other hand, the overall framework within which we make these kinds of value judgments, right? So where does that leave us?

Well, with another variation on the old subjective/objective thing, I suppose. In other words, it's ineffable.

* * *

1. Bachelor No 2, or The Last Remains of the Dodo - Aimee Mann

2. OK Computer - Radiohead

3. Loveless - My Bloody Valentine

4. Treasure - Cocteau Twins

5. Blue Bell Knoll - Cocteau Twins

6. The Velvet Underground & Nico - The Velvet Underground & Nico

7. Moon Pix - Cat Power

8. On Fire - Galaxie 500

9. New Adventures In Hi-Fi - R.E.M.

10. Summerteeth - Wilco

11. Homogenic - Björk

12. Isn't Anything - My Bloody Valentine

13. The Queen Is Dead - The Smiths

14. The Bends - Radiohead

15. Psychocandy - The Jesus and Mary Chain

16. Closer - Joy Division

17. Funeral - The Arcade Fire

18. Disintegration - The Cure

19. f#a#∞ - Godspeed You Black Emperor!

20. Blacklisted - Neko Case

Raymond E Feist - Prince of the Blood

Have done some serious damage to my sleep patterns in the last few weeks, to the extent that it's now difficult to sleep any time before 4, with 5 or 5.30 being more common (it's always a worry when you're trying to fall asleep as the sky outside is beginning to grow lighter).[*] Some nights, I can more or less push on with Heidegger pretty much till then (albeit not as efficiently as at more sane times of day/night), but on other nights, this leaves me with some dead time between shutting up shop for the night and actually being able to fall asleep. Last night was one such, and I really needed a break from the paper-writing to allow my thoughts to settle and take shape, all of which is to explain why I sat up and re-read what is really a particularly mediocre entry in the Feist oeuvre (I picked it up about a quarter of the way in, having read the first quarter or so relatively recently) - an oeuvre which is, incidentally, not particularly mediocre as a whole, as far as it goes - mainly on the basis that it'd be thoroughly undemanding and I didn't already know it absolutely inside out (unlike most of the other undemanding books on my shelf).

* * *

[*] Actually, I suspect that there are a host of other factors bleeding into this inability to sleep, but they all kind of aggregate and compound in - or are compounded by - the brute fact of not having slept properly in recent times.

* * *

[*] Actually, I suspect that there are a host of other factors bleeding into this inability to sleep, but they all kind of aggregate and compound in - or are compounded by - the brute fact of not having slept properly in recent times.

Sunday, November 13, 2005

"And death shall have no dominion": Solaris

[Edited 14/7/19 to remove some personal content]

Actually, this time round it seemed more of a sci-fi film than a metaphysical one (and no, I'm not trying to draw bright lines between the two). I've never been much of a reader of sci-fi, but I've dipped in from time to time, and once in a while a book in the genre (I don't really remember names, but I think that Greg Bear may've written one or two) has given me a strange, dislocated sort of feeling, as if I really am reading about a kind of refracted reality - plausible but distorted (perhaps the word I'm looking for is 'uncanny' - unheimlich), making me feel as if the ground is shifting beneath my feet. Anyway, Solaris made me feel like that.

See, the first time I watched the film, I was thinking more in terms of it exploring the nature of reality and its interaction with consciousness (phenomenology again, though this would've been before I formally studied 'phenomenology and existentialism', I think), but this time round, Solaris seemed more like a 'sci-fi' concept around which was built a recognisably humanistic moral and rational core (again, not that this and 'metaphysics' are mutually exclusive).

The mood it creates is really something, and it looks and feels exactly as it should. It's artfully done - the way that memories and perceptual streams are shot as formally disconnected yet fade into each other (the device of the visuals dropping away while dialogue continues is an effective one) and also the structuring of the film as a whole, particularly the repetitions...all quite dream-like, or memory-like, or maybe simply everyday experience-like, when you stop to reflect on it.