Last night was feeling too flat to do anything but a little restless at the same time, so I took off for Carlton with the intention of catching a late show at the Nova on my own. Was tossing up between Mirrormask, Serenity and Broken Flowers (and briefly considered The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe when I unexpectedly arrived early enough for that 'un), but once I got to the cinema, I realised that in the circumstances (drifting, late at night, alone) the new Jarmusch was the only possible choice.

The set-up of the film's quite simple - Don Johnston (Bill Murray), an aging bachelor with a string of relationships behind him, has just been left by his latest, and on the same day receives a letter from an anonymous ex informing him he has a 19 year old son who may have set out on a road trip in search of him. Spurred by his detective fiction-fascinated neighbour Winston, he goes on a road trip of his own, riding buses, renting cars and flying on airplanes across the US in order to drop in on old lovers, searching for clues as to which - if any - might be the mother of his son.

In some ways, the tenor for Don's interactions with these old flames is set by the scene with his most recent, Shelly (played by Julie Delpy), whose departure kicks off the journey. They talk - a little - and there are hints of communication and understanding there, both in what is said and what is not, but it's overhung by a heaviness - the heaviness of the past and, it seems, of Don's inability or unwillingness to open up or give something essential of himself. Moreover, Delpy must be one of the most beautiful women in film today, and that beauty can be seen in her character in Broken Flowers, but something about her here - her appearance, her character, her performance - gives an impression of her as a woman who has seen a bit of and, in some measure, been let down by life...she appears weary in a way which can't be completely attributed to her relationship with Don.

The same is true of the ex-lovers whom Don drops in on, one by one: Laura (Sharon Stone), a brightly smiling but somehow brittle suburban single mother, her husband having died in a fiery accident; Dora (Frances Conroy), a former hippie princess turned childless, dessicated, quietly suffocating housewife in an immaculate, prefab house; Carmen (Jessica Lange), who became a successful lawyer after her time with Don, before giving it up for a new career as an 'animal communicator'; and Penny (Tilda Swinton), fiery and bruised, living in trailer-parkville surrounded by motorbikes, trash and wildflowers (and there's also one other who has passed away, and whose grave Don visits last, on a rainy day). With the exception of Conroy, all of them are familiar faces to me, but they're familiar as younger, fresher faces, and in Broken Flowers all have the same faded air of having suffered their own private heartaches and regrets as the years have passed - which is given added piquancy by the clear images of their younger selves which are so easy to summon. (They're all fantastic - especially Stone.)

The centre of the film is, of course, Don, and this centre is occupied by Murray, as it was in Lost In Translation (and, to a lesser extent, The Life Aquatic), with a weary passivity which is saved from being mere nullity by the understated hints of feeling which he conveys - vulnerability, regret, nostalgia, doubt. It's a subtle and nuanced performance, and if one often feels that Murray is basically just playing Bill Murray, well, that's probably all to the good in this case. Don isn't the sort of character who talks a lot about his feelings, or ever seems to be taking an active part in the direction of his life, and yet, as the film progresses, one senses (or intuits) a great deal of what he's thinking, and what directions he's moving in as a person as the trip goes on...and he's definitely a character - a real person - and not simply a cipher or an abstract riddle to be solved or decoded.

In that respect, an important hint is provided by the significance of the colour pink. The letter which triggers the whole journey comes in a pink envelope, and is typewritten on pink paper (red ink for the handwritten address on the envelope), and the colour (along with the typewriter) comes to be a recurring theme in Don's journey. Not only does he always bring pink flowers, but every one of the women (including Shelly) is somehow identified with the colour, whether by clothing, possessions, or other means - giving rise to the suspicion that perhaps Don's perceptions are being quite literally coloured by his expectations and desires...that the vision we're getting in Broken Flowers is a subtly fantasised one, shaped by the personality and submerged wishes of Don himself (a theme also played out in Don's reactions to the young men with whom he crosses paths, each of whom just may be his son).

A couple of other comments: the bluesy, 60s-styled song playing at the beginning (done by an outfit called the Greenhornes, with Holly Golightly on vocals) was ace, and music is important throughout the film; the whole film has a very cool, arty feel, and its episodic style worked in its favour, I thought, particularly when coupled with the fade out/fade ins used as transitions between episodes; it's also very funny and often very warm (say, in Don's interactions with Winston's family); and the ending is, while a bit predictable, the right one. There are hints as to the truth of the letter and its author, and I have some theories about that myself, but in the end, that question isn't really the mystery with which Jarmusch or Broken Flowers is concerned. So all up, I thought that this was a good little piece - it didn't take my breath away, but it's lingered with me so far, and I want to see it again.

* * *

Incidentally, having gone out at that time also gave me the opportunity to indulge in one of my more idiosyncratic pleasures - wandering through the aisles of a supermarket at night (the film started at 11.40pm, and the Safeway in the complex closes at midnight). I know, very DeLillo of me - but I think that the appeal comes from the slightly weird-surreal-incongruous nature of the exercise, rather than out of any sense of self-construction through consumption, conspicuous mediation of everyday experience, or et cetera. Did think about buying something - considered a tin of Campbell's tomato soup (420g; $1.84), as a sort of salute to Warhol - though, and in the end settled for an apple to crunch on before the film started.

Friday, December 30, 2005

Thursday, December 29, 2005

8 Femmes

So anyway, having been at the Immigration Museum and generally out and about during the afternoon, I found myself alone at 5.30 and repaired to one of my city watering holes (Murmur) for a few glasses of wine and a few chapters of The Counterfeiters. Arriving home a bit later, it occurred to me that this might be a suitable state in which to renew my acquaintance with François Ozon's delightful and confounding 8 Femmes (a film which really demands its French title, I reckon).

I don't even know where to begin writing about this film - it's just so very. (Penny once said that she found it terrifying, and I can see where she was coming from, though I can't put the reasons for it into words.) The colours are a big part of it - each character has an Outfit (in a couple of cases, more than one) and bright doesn't begin to describe them (nor the set design)...everything is immaculate. The gleefully, ridiculously melodramatic way in which Ozon piles revelation upon revelation upon revelation reminds us that we're watching a farce...and then there are the musical numbers. I bought the soundtrack straight after watching 8 Femmes the first time round, but even the familiarity with the music that that's brought didn't dilute the effect of seeing these eight women take it in turns to break into song, complete with over the top gestures and dramatic acting (in fact, if anything, it made it even more surreal). Nearly every time it happened, I started laughing - I couldn't help myself. It's just so sublimely weird.

Then, too, there are so many scenes to savour - Virginie Ledoyen and Emmanuelle Beart icily circling each other (the latter pouting, as she does throughout the film, as if her life depended on it), the grand old dame Catherine Deneuve and Fanny Ardant rolling around and grappling undignifiedly on the carpet (first le cat fight, then le sapphism...again), Isabelle Huppert going into repressed-spinster hysterics...and a thousand tiny little interactions - the one that comes to mind is Ardant puffing smoke in the face of Ledoyen, and the offended mini-flounce away with which the latter responds...though the moment when Deneuve breaks a bottle over Danielle Darrieux's head is pretty good, too.

Brightly candy-coloured and very funny, yes, but 8 Femmes has a darkness at its heart (in fact, as soon as one stops to think about what the characters are actually doing, and have done, and have had done to them, it comes to seem positively horrific). As the final song goes, il n'y a pas d'amour heureux, but the film's dark vision extends well beyond the tricks that love etc can play. And somehow, too (and I've no idea how Ozon does this, unless it's simply the cheap tricks and easy pathos of melodrama - and I don't think that it is), the viewer is brought to sympathise with the characters. When Huppert sang her song, I felt misty-eyed; when Firmine Richard was scorned, I felt her hurt; and so on with all of them, as their secrets are brought out into the light, one by one.

In case it isn't obvious, I love this film. And I've never seen anything at all like it.

I don't even know where to begin writing about this film - it's just so very. (Penny once said that she found it terrifying, and I can see where she was coming from, though I can't put the reasons for it into words.) The colours are a big part of it - each character has an Outfit (in a couple of cases, more than one) and bright doesn't begin to describe them (nor the set design)...everything is immaculate. The gleefully, ridiculously melodramatic way in which Ozon piles revelation upon revelation upon revelation reminds us that we're watching a farce...and then there are the musical numbers. I bought the soundtrack straight after watching 8 Femmes the first time round, but even the familiarity with the music that that's brought didn't dilute the effect of seeing these eight women take it in turns to break into song, complete with over the top gestures and dramatic acting (in fact, if anything, it made it even more surreal). Nearly every time it happened, I started laughing - I couldn't help myself. It's just so sublimely weird.

Then, too, there are so many scenes to savour - Virginie Ledoyen and Emmanuelle Beart icily circling each other (the latter pouting, as she does throughout the film, as if her life depended on it), the grand old dame Catherine Deneuve and Fanny Ardant rolling around and grappling undignifiedly on the carpet (first le cat fight, then le sapphism...again), Isabelle Huppert going into repressed-spinster hysterics...and a thousand tiny little interactions - the one that comes to mind is Ardant puffing smoke in the face of Ledoyen, and the offended mini-flounce away with which the latter responds...though the moment when Deneuve breaks a bottle over Danielle Darrieux's head is pretty good, too.

Brightly candy-coloured and very funny, yes, but 8 Femmes has a darkness at its heart (in fact, as soon as one stops to think about what the characters are actually doing, and have done, and have had done to them, it comes to seem positively horrific). As the final song goes, il n'y a pas d'amour heureux, but the film's dark vision extends well beyond the tricks that love etc can play. And somehow, too (and I've no idea how Ozon does this, unless it's simply the cheap tricks and easy pathos of melodrama - and I don't think that it is), the viewer is brought to sympathise with the characters. When Huppert sang her song, I felt misty-eyed; when Firmine Richard was scorned, I felt her hurt; and so on with all of them, as their secrets are brought out into the light, one by one.

In case it isn't obvious, I love this film. And I've never seen anything at all like it.

"Greek Treasures from the Benaki Museum in Athens" @ Immigration Museum (and some art of my own)

A collection of art and craft-type objects from Greece, stretching back to something like 6000 BC - clay work (pots, vases, fertility icons, etc), gold jewellery, religious silverwork, carved wood in various forms (chests, windows, representations of gods and goddesses...), colourful bridal attire, arrowheads and other weapons (my favourites - I can be a bit of a boy about these things sometimes), some rather exquisite ancient books, and later various paintings (watercolour, lithographs, oil) depicting key moments in the formation of the Greek nation and its various struggles for independence (including one of Byron).

I didn't really respond to most of it as 'art', mainly, I guess, because it's not what I'm accustomed to thinking of as art. (Besides, the the ancient Greeks didn't distinguish between 'art' and 'crafts' - something I picked up from reading Aristotle...who says that philosophy has no relevance to the real world? - so there's a double sense in which these pieces could only ever be retrospectively identified as such.) But it was interesting to wander through, looking at the artifacts, and realise how deeply these kinds of images are ingrained into our collective (western) set of cultural references - how immediately familiar it all seemed. And, of course, there's a certain 'wow' factor in realising how old some of the stuff was, and imagining that, say, 4000 years ago, someone was actually wearing these bracelets or those shoes, or trying to shoot this arrow into someone else...

So afterwards we wandered through the main collection (which I hadn't had a chance to fully suss out last time I was at the museum); one thing which wasn't there last time was a table, supplied with scraps of coloured paper and crepe, kid-safe scissors (those funny stubby ones from primary school), glue sticks, and pre-cut paper homunculi, with an invitation for passers-by to sit down and make their own Australians to velcro to a cloth board standing nearby. So naturally I sat down to create an avatar of myself - black and red horizontally-striped sweater, insouciantly wrapped blue scarf, grey stovepipe pants (black would've been better, but there wasn't enough black paper...also, I had to trim the human shape provided, to make the hips more snake-like and the legs thinner and more à la façon), a hint of black and white striped socks, and brown loafers. (Obviously this was the highlight of my visit.) By contrast, Wei - who managed two in the time that it took me to make one - came up with (1) a spiky pink-haired lesbian-looking androgyne (although admittedly the pink hair was suggested by the little girl who was sitting opposite us at the time) and (2) a rather glam Jackie O type, though looking as if she was dressed (and made up) for a 1920s-themed party. Presumably these were not avatars of hers. Anyway, they're all on display in the museum now, for the edification of the general public...

I didn't really respond to most of it as 'art', mainly, I guess, because it's not what I'm accustomed to thinking of as art. (Besides, the the ancient Greeks didn't distinguish between 'art' and 'crafts' - something I picked up from reading Aristotle...who says that philosophy has no relevance to the real world? - so there's a double sense in which these pieces could only ever be retrospectively identified as such.) But it was interesting to wander through, looking at the artifacts, and realise how deeply these kinds of images are ingrained into our collective (western) set of cultural references - how immediately familiar it all seemed. And, of course, there's a certain 'wow' factor in realising how old some of the stuff was, and imagining that, say, 4000 years ago, someone was actually wearing these bracelets or those shoes, or trying to shoot this arrow into someone else...

So afterwards we wandered through the main collection (which I hadn't had a chance to fully suss out last time I was at the museum); one thing which wasn't there last time was a table, supplied with scraps of coloured paper and crepe, kid-safe scissors (those funny stubby ones from primary school), glue sticks, and pre-cut paper homunculi, with an invitation for passers-by to sit down and make their own Australians to velcro to a cloth board standing nearby. So naturally I sat down to create an avatar of myself - black and red horizontally-striped sweater, insouciantly wrapped blue scarf, grey stovepipe pants (black would've been better, but there wasn't enough black paper...also, I had to trim the human shape provided, to make the hips more snake-like and the legs thinner and more à la façon), a hint of black and white striped socks, and brown loafers. (Obviously this was the highlight of my visit.) By contrast, Wei - who managed two in the time that it took me to make one - came up with (1) a spiky pink-haired lesbian-looking androgyne (although admittedly the pink hair was suggested by the little girl who was sitting opposite us at the time) and (2) a rather glam Jackie O type, though looking as if she was dressed (and made up) for a 1920s-themed party. Presumably these were not avatars of hers. Anyway, they're all on display in the museum now, for the edification of the general public...

Tuesday, December 27, 2005

Down From The Mountain

A dvd, recording a concert that took place after O Brother, Where Art Thou? had been completed but (I think) before it had been released and definitely before its soundtrack had become a huge hit. It's mostly music from the film itself; I got a real kick out of seeing Gillian Welch in particular (exactly as I'd imagined her from the albums and associated photos - slightly awkward, a bit gangly, warm, and lovely-seeming), but it was somethin' to see Emmylou Harris and Alison Krauss doing their thing live as well (got a bit of a chill during Emmylou's rendering of the traditional number "Green Pastures", and Alison Krauss' a cappella intro to "Down To The River To Pray" was also a bit special, showcasing her voice as it did). As a bonus, Welch and partner David Rawlings did two non-movie songs on top of their O Brother collaborations - "My Dear Someone" and "I Want To Sing That Rock & Roll". Both were very similar to the album versions, but breathed with a little something else in the live setting.

The show was compered by the fiddler John Hartford, one of those interesting and humane-looking old men, who also performed (the interaction between he and Welch during their performance of "Indian War Whoop" brought a smile to my face). Also featured are the Cox Family, the Whites, Ralph Stanley (receiving a standing ovation when he first came on stage), and others. Impossible not to respond to music so unaffected, pure and rich - there's an almost tangible good humour and warmth to the whole concert, and I was left with a warm feeling myself, as well as a quiet, inexpressible sense of something approaching wonder at the endurance and strange power of music, and this mountain-rooted music in particular.

The show was compered by the fiddler John Hartford, one of those interesting and humane-looking old men, who also performed (the interaction between he and Welch during their performance of "Indian War Whoop" brought a smile to my face). Also featured are the Cox Family, the Whites, Ralph Stanley (receiving a standing ovation when he first came on stage), and others. Impossible not to respond to music so unaffected, pure and rich - there's an almost tangible good humour and warmth to the whole concert, and I was left with a warm feeling myself, as well as a quiet, inexpressible sense of something approaching wonder at the endurance and strange power of music, and this mountain-rooted music in particular.

Monday, December 26, 2005

Zadie Smith - The Autograph Man

Alright, the case against The Autograph Man has many elements, but basically it boils down to this: it's too damn obvious. I more or less like it notwithstanding, but it's probably telling that I thought exactly the same things about it on this reading as I did the first time round, a few years back.

Lessee...to begin with, naming one's central character 'Alex' (ie, 'without words') and then making him a dealer in autographs (ie, the word, or sign, or signifier, of a person), might well be construed as Hitting The Reader Over The Head, never mind the numerous overt references to signs and signification which are scattered throughout the novel. Then, too, the novel employs what might be called the DeLillo strategy - start off with an obvious central conceit (see above), and then 'develop' it with lots of single scene or even single sentence instances of the same basic point. Which is all very clever, and wonderful grist for the mill of academic writing, but in the end not terribly satisfying for the reader ("oh look, yet again the sign has been confused for the reality"...ho hum).

Then, don't waste any time quoting Benjamin's famous definition of aura at the beginning of the first chapter proper (calling him a 'popular wise guy', because of course you're going to be irreverent), and then work references to him into the text (because of course you're going to get the intertextuality going). Then connect this up to the autograph business, and in particular Alex's (well, Alex-Li's, actually) fixation on one particular screen actress of the past, Kitty Alexander (nostalgia, don't you know?), and then have him actually meet her, and look: authenticity (or some simulacrum of it?)!

But hold on. Things are getting a bit more complicated here. Detachment of signifier from signified, yes. Hyperreality not reality, yes. Mediation not authentic experience, yes. Aura not object, yes. All very obvious - but. But the way they all come together in The Autograph Man - that's a bit more interesting. Plus, Alex-Li is Jewish, and much of the rest of the novel is concerned with his attempts to come to terms with this, and the various approaches of his friends to the same questions of identity and faith, and to arrive at a sort of authentic experience of, or insight into, the world. (And hang on, Benjamin was Jewish as well, right? Famous (ahem) for it.)

Now, a novel cannot survive on ideas alone - what about the story, the characters? Alack, in The Autograph Man, the characters are somewhat submerged beneath the ideas - rather ironically, to some extent they become mere signs themselves, rather than fully fleshed-out subjects in their own right. One never feels - as one always does in reading White Teeth (well, except maybe with the Chalfens) - that these are quite real people; they somehow don't quite come to life in the same way. There's not that much of a story...but I've never minded that in a novel.

All that said, this is still a funny, lively, easy-to-read novel, and while I may have criticised it for being a bit obvious, I do think that it has many virtues, and overall I think I like it, though I can't imagine wanting to read it a third time any time soon. As it happens, the day after I borrowed this from the City Library, I was in the Shoppingtown library and picked up On Beauty; I've refrained from starting that latter until finishing The Autograph Man, but word on it is good (Booker nominated, no less!)...

Lessee...to begin with, naming one's central character 'Alex' (ie, 'without words') and then making him a dealer in autographs (ie, the word, or sign, or signifier, of a person), might well be construed as Hitting The Reader Over The Head, never mind the numerous overt references to signs and signification which are scattered throughout the novel. Then, too, the novel employs what might be called the DeLillo strategy - start off with an obvious central conceit (see above), and then 'develop' it with lots of single scene or even single sentence instances of the same basic point. Which is all very clever, and wonderful grist for the mill of academic writing, but in the end not terribly satisfying for the reader ("oh look, yet again the sign has been confused for the reality"...ho hum).

Then, don't waste any time quoting Benjamin's famous definition of aura at the beginning of the first chapter proper (calling him a 'popular wise guy', because of course you're going to be irreverent), and then work references to him into the text (because of course you're going to get the intertextuality going). Then connect this up to the autograph business, and in particular Alex's (well, Alex-Li's, actually) fixation on one particular screen actress of the past, Kitty Alexander (nostalgia, don't you know?), and then have him actually meet her, and look: authenticity (or some simulacrum of it?)!

But hold on. Things are getting a bit more complicated here. Detachment of signifier from signified, yes. Hyperreality not reality, yes. Mediation not authentic experience, yes. Aura not object, yes. All very obvious - but. But the way they all come together in The Autograph Man - that's a bit more interesting. Plus, Alex-Li is Jewish, and much of the rest of the novel is concerned with his attempts to come to terms with this, and the various approaches of his friends to the same questions of identity and faith, and to arrive at a sort of authentic experience of, or insight into, the world. (And hang on, Benjamin was Jewish as well, right? Famous (ahem) for it.)

Now, a novel cannot survive on ideas alone - what about the story, the characters? Alack, in The Autograph Man, the characters are somewhat submerged beneath the ideas - rather ironically, to some extent they become mere signs themselves, rather than fully fleshed-out subjects in their own right. One never feels - as one always does in reading White Teeth (well, except maybe with the Chalfens) - that these are quite real people; they somehow don't quite come to life in the same way. There's not that much of a story...but I've never minded that in a novel.

All that said, this is still a funny, lively, easy-to-read novel, and while I may have criticised it for being a bit obvious, I do think that it has many virtues, and overall I think I like it, though I can't imagine wanting to read it a third time any time soon. As it happens, the day after I borrowed this from the City Library, I was in the Shoppingtown library and picked up On Beauty; I've refrained from starting that latter until finishing The Autograph Man, but word on it is good (Booker nominated, no less!)...

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou

I quite liked this, but, as with The Royal Tenenbaums, I felt that Anderson was trying to have it both ways - he wants to present a skewed, surreal narrative, peopled by semi-caricatures, in which the artifice of the medium is foregrounded (eg, the absurdly brightly coloured sea animals, the cutaway views of the ship, the obvious fakeness of the pirates' weapons, the cliché 'action' sequences), and make an affecting, character and relationship-driven piece at the same time. The result is interesting and often amusing, but ultimately unconvincing (though I must admit that the finale, in which nearly the whole of the cast, sans Owen Wilson, crams into the submarine and comes face to face the glowing jaguar shark to the strains of - appropriately enough - Sigur Ros' "Staralfur", worked for me). Tops cast, though.

Sunday, December 25, 2005

Virginia Woolf - To The Lighthouse

"But this is what I see; this is what I see,"

I felt this about Mrs Dalloway, but it's struck me even more strongly with To The Lighthouse - this is a novel about life, and simply what it is to be alive (how strange and wonderful to be anything at all). It's about sadness and happiness, moments and eternity, stillness and change, solitude and merging, disconnectedness and communication, the spaces between people and what exists in those spaces. It's precise, detailed, dreamy, ethereal, undeniable.

Reading To The Lighthouse had me reflecting on my own life, and it's scattered with moments of recognition both acute and general; the novel constantly stopped me in my tracks, as over and over I hit passages which perfectly reflected my own thoughts and experiences of the world. It's not just the ideas themselves - it's the expression, too. For it gives expression to the world as presented to consciousness - a kind of phenomenology - while illuminating both, revealing the profound and essential connection between subjective experience and the world at large, and at the same time also making sense of how we come to terms with other people, also wandering through these thickets.

Some passages which particularly resonated:

I. They both smiled, standing there. They both felt a common hilarity, excited by the moving waves; and then by the swift cutting race of a sailing boat, which, having sliced a curve in the bay, stopped; shivered; let its sails drop down; and then, with a natural instinct to complete the picture, after this swift movement, both of them looked at the dunes far away, and instead of merriment came over them some sadness - because the thing was completed partly, and partly because distant views seem to outlast by a million years (Lily thought) the gazer and to be communing already with a sky which beholds an earth entirely at rest. (20)

II. How then did it work out, all this? How did one judge people, think of them? How did one add up this and that and conclude that it was liking one felt, or disliking? And to those words, what meaning attached, after all? Standing now, apparently transfixed, by the pear tree, impressions poured in upon her of those two men, and to follow her thought was like following a voice which speaks too quickly to be taken down by one's pencil, and the voice was her own voice saying without prompting undeniable, everlasting, contradictory things, so that even the fissures and humps on the bark of the pear tree were irrevocably fixed there for eternity. (24)

III. And, what was even more exciting, she felt, too, as she saw Mr. Ramsay bearing down and retreating, and Mrs. Ramsay sitting with James in the window and the cloud moving and the tree bending, how life, from being made up of little separate incidents which one lived one by one, became curled and whole like a wave which bore one up with it and threw one down with it, there, with a dash on the beach. (47)

IV. To be silent; to be alone. all the being and the doing, expansive, glittering, vocal, evaporated; and one shrunk, with a sense of solemnity, to being oneself, a wedge-shaped core of darkness, something invisible to others. (62)

V. And suddenly the meaning which, for no reason at all, as perhaps they are stepping out of the Tube or ringing a doorbell, descends on people, making them symbolical, making them representative, came upon them, and made them in the dusk standing, looking, the symbols of marriage, husband and wife. (72)

VI. The room (she looked round it) was very shabby. There was no beauty anywhere. She forbore to look at Mr. Tansley. Nothing seemed to have merged. They all sat separate. And the whole of the effort of merging and flowing and creating rested on her. (83)

VII. Everything seemed possible. Everything seemed right. Just now (but this cannot last, she thought, dissociating herself from the moment while they were all talking about boots) just now she had reached security; she hovered like a hawk suspended; like a flag floated in an element of joy which filled every nerve of her body fully and sweetly, not noisily, solemnly rather, for it arose, she thought, looking at them all eating there, from husband and children and friends; all of which rising in this profound stillness (she was helping William Bankes to one very small piece more, and peered into the depths of the earthenware pot) seemed now for no special reason to stay there like a smoke, like a fume rising upwards, holding them safe together. Nothing need be said; nothing could be said. There it was, all round them. It partook, she felt, carefully helping Mr. Bankes to a specially tender piece, of eternity; as she has already felt about something different once before that afternoon; there is a coherence in things, a stability; something, she meant, is immune from change, and shines out (she glanced at the window with its ripple of reflected lights) in the face of the flowing, the fleeting, the spectral, like a ruby; so that again tonight she had the feeling she had had once today, already, of peace, of rest. Of such moments, she thought, the thing is made that endures. (105)

Those are all from the first part of the novel, 'The Window', which figures, for it's in that first part that all of these seeds are planted. In the second, 'Time Passes', change descends and time does, indeed, pass; and in the third, 'The Lighthouse', a resolution is reached and one is left with the feeling that, as Mrs Ramsay exclaims somewhere, earlier, and in her mind, it is enough.

* * *

One wanted, she thought, dipping her brush deliberately, to be on a level with ordinary experience, to feel simply that's a chair, that's a table, and yet at the same time, It's a miracle, it's an ecstasy. The problem might be solved after all.

[...]

Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.

* * *

A few notes:

- The reading of To The Lighthouse tempted me to change my own (still only in the planning stages) novel from first to third person voice, but I think that the temptation has passed, at least for the time being (perhaps re-reading some Murakami, or finally digging into Proust, will fortify me in that regard).

- The book was a gift from Penny years ago; I started on it at the time but bogged down about 30 pages in...I think that it's taken me all this time to get to the point where I can really begin to appreciate it; now, it's gone straight on to my list of favourites.

- It's taken me much longer to finish than is usual for me - more than a month, I think (goes without saying that I've read a lot else in that time, but even so...) - mainly because I wanted to give it my full attention whenever I was reading it, and really to savour it. Had twenty or so pages to go today (after a break of about a week), and thought that Christmas Day might be an appropriate date on which to finish it.

I felt this about Mrs Dalloway, but it's struck me even more strongly with To The Lighthouse - this is a novel about life, and simply what it is to be alive (how strange and wonderful to be anything at all). It's about sadness and happiness, moments and eternity, stillness and change, solitude and merging, disconnectedness and communication, the spaces between people and what exists in those spaces. It's precise, detailed, dreamy, ethereal, undeniable.

Reading To The Lighthouse had me reflecting on my own life, and it's scattered with moments of recognition both acute and general; the novel constantly stopped me in my tracks, as over and over I hit passages which perfectly reflected my own thoughts and experiences of the world. It's not just the ideas themselves - it's the expression, too. For it gives expression to the world as presented to consciousness - a kind of phenomenology - while illuminating both, revealing the profound and essential connection between subjective experience and the world at large, and at the same time also making sense of how we come to terms with other people, also wandering through these thickets.

Some passages which particularly resonated:

I. They both smiled, standing there. They both felt a common hilarity, excited by the moving waves; and then by the swift cutting race of a sailing boat, which, having sliced a curve in the bay, stopped; shivered; let its sails drop down; and then, with a natural instinct to complete the picture, after this swift movement, both of them looked at the dunes far away, and instead of merriment came over them some sadness - because the thing was completed partly, and partly because distant views seem to outlast by a million years (Lily thought) the gazer and to be communing already with a sky which beholds an earth entirely at rest. (20)

II. How then did it work out, all this? How did one judge people, think of them? How did one add up this and that and conclude that it was liking one felt, or disliking? And to those words, what meaning attached, after all? Standing now, apparently transfixed, by the pear tree, impressions poured in upon her of those two men, and to follow her thought was like following a voice which speaks too quickly to be taken down by one's pencil, and the voice was her own voice saying without prompting undeniable, everlasting, contradictory things, so that even the fissures and humps on the bark of the pear tree were irrevocably fixed there for eternity. (24)

III. And, what was even more exciting, she felt, too, as she saw Mr. Ramsay bearing down and retreating, and Mrs. Ramsay sitting with James in the window and the cloud moving and the tree bending, how life, from being made up of little separate incidents which one lived one by one, became curled and whole like a wave which bore one up with it and threw one down with it, there, with a dash on the beach. (47)

IV. To be silent; to be alone. all the being and the doing, expansive, glittering, vocal, evaporated; and one shrunk, with a sense of solemnity, to being oneself, a wedge-shaped core of darkness, something invisible to others. (62)

V. And suddenly the meaning which, for no reason at all, as perhaps they are stepping out of the Tube or ringing a doorbell, descends on people, making them symbolical, making them representative, came upon them, and made them in the dusk standing, looking, the symbols of marriage, husband and wife. (72)

VI. The room (she looked round it) was very shabby. There was no beauty anywhere. She forbore to look at Mr. Tansley. Nothing seemed to have merged. They all sat separate. And the whole of the effort of merging and flowing and creating rested on her. (83)

VII. Everything seemed possible. Everything seemed right. Just now (but this cannot last, she thought, dissociating herself from the moment while they were all talking about boots) just now she had reached security; she hovered like a hawk suspended; like a flag floated in an element of joy which filled every nerve of her body fully and sweetly, not noisily, solemnly rather, for it arose, she thought, looking at them all eating there, from husband and children and friends; all of which rising in this profound stillness (she was helping William Bankes to one very small piece more, and peered into the depths of the earthenware pot) seemed now for no special reason to stay there like a smoke, like a fume rising upwards, holding them safe together. Nothing need be said; nothing could be said. There it was, all round them. It partook, she felt, carefully helping Mr. Bankes to a specially tender piece, of eternity; as she has already felt about something different once before that afternoon; there is a coherence in things, a stability; something, she meant, is immune from change, and shines out (she glanced at the window with its ripple of reflected lights) in the face of the flowing, the fleeting, the spectral, like a ruby; so that again tonight she had the feeling she had had once today, already, of peace, of rest. Of such moments, she thought, the thing is made that endures. (105)

Those are all from the first part of the novel, 'The Window', which figures, for it's in that first part that all of these seeds are planted. In the second, 'Time Passes', change descends and time does, indeed, pass; and in the third, 'The Lighthouse', a resolution is reached and one is left with the feeling that, as Mrs Ramsay exclaims somewhere, earlier, and in her mind, it is enough.

* * *

One wanted, she thought, dipping her brush deliberately, to be on a level with ordinary experience, to feel simply that's a chair, that's a table, and yet at the same time, It's a miracle, it's an ecstasy. The problem might be solved after all.

[...]

Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.

* * *

A few notes:

- The reading of To The Lighthouse tempted me to change my own (still only in the planning stages) novel from first to third person voice, but I think that the temptation has passed, at least for the time being (perhaps re-reading some Murakami, or finally digging into Proust, will fortify me in that regard).

- The book was a gift from Penny years ago; I started on it at the time but bogged down about 30 pages in...I think that it's taken me all this time to get to the point where I can really begin to appreciate it; now, it's gone straight on to my list of favourites.

- It's taken me much longer to finish than is usual for me - more than a month, I think (goes without saying that I've read a lot else in that time, but even so...) - mainly because I wanted to give it my full attention whenever I was reading it, and really to savour it. Had twenty or so pages to go today (after a break of about a week), and thought that Christmas Day might be an appropriate date on which to finish it.

George R R Martin - A Feast For Crows

I thought that there was a slight dropping off in the quality of this one - to an extent, Martin seems to be going through the motions - but this fourth book in the series is still a high quality example of its type and definitely kept my interest all the way through, leaving me wanting the next book asap. Here, the scope of the series widens, with Dorne becoming more significant; in fact, several important strands of the story are wholly or completely left out of A Feast For Crows. Not sure if I can manage to tick them all off, but the most notable of these are, I think, to do with events on and around the Wall (involving Jon Snow, King Stannis and Melisandre, not to mention those seeking to work their intrigues around them, and Bran's voyage north of the Wall) and Dany's rule across the sea. Also no word of Tyrion (except through Cersei's attempts to find him), Theon Greyjoy (I can't remember what had become of him by the end of the previous book - held by Roose Bolton at the Dreadfort, or still in Winterfell, or something else?), Davos Seaworth (barring a report that he has been killed, which I do not believe and expect to learn in later books was a false report), Rickon, or any of the direwolves.

As to those who do appear in this book, I feel that I should briefly set down how things stand, to aid me in picking up the next book, whenever it should come out.

- Cersei has succeeded in having Margaery imprisoned on charges of infidelity, only to herself be thrown into jail at the behest of the new High Septon; the boy King Tommen still sits the throne.

- Jaime, who has succeeded in taking Riverrun bloodlessly from Brynden Tully (only for the Blackfish to escape during the handover), has refused Cersei's desperate plea for help.

- Ser Lancel has left Darry to join the newly constituted militant religious order.

- Loras Tyrell is on the verge of death after leading a successful assault on Dragonstone, previously held by Stannis.

- Sandor Clegane really is dead of his wounds, it seems (though I'm not entirely convinced of this, either).

- Petyr Baelish continues to manoeuver from the Eyrie, where Sansa stays under the name 'Alayne', posing as his natural daughter and young Richard Arryn also remains.

- Arya, in training in a Braavosi temple, has just been blinded by a man of the temple after committing murder.

- Brienne, still seeking Sansa, has fallen into the hands of a group of outlaws - splinters from Beric Dondarrion's raiders (there are hints that Beric himself may finally be dead, but maybe not) - led by Catelyn, who is horribly disfigured but alive, and made to choose between killing Jaime and hanging herself.

- Samwell has made his way to Oldtown, where he has told his tale to an archmaester, Marwyn, who has then set off to counsel Dany.

- Euron Crow's Eye has succeeded to the title of King of the Iron Islands and is raiding in force up the Mander; Victarion remains loyal to him, but Aeron and Asha have both fled.

- And the old Prince of Dorne, Doran Martell, seems to be playing a deeper game than even his own family had suspected; Princess Myrcella Baratheon, his ward, has been seriously wounded.

I'm not even going to try to set out who currently holds which castle or title, or who's where, or what's happening with all of the minor characters who seem likely to still have large roles to play in what's to come - the Freys, the Corbrays, the Kettleblacks, Mace Tyrell, Lord Nestor, Yohn Royce, Lady Merryweather, Edmure Tully, Kevan Lannister, Walder Rivers, Randyll Tarly, Aurane Waters, Bronn, Qyburn, Pycelle, Gendry...this series is massive. But one of its great virtues is Martin's ability to characterise all these figures, and keep them turning over so that now one rises to prominence, now another - and while we may guess, we never know quite what's coming.

As to those who do appear in this book, I feel that I should briefly set down how things stand, to aid me in picking up the next book, whenever it should come out.

- Cersei has succeeded in having Margaery imprisoned on charges of infidelity, only to herself be thrown into jail at the behest of the new High Septon; the boy King Tommen still sits the throne.

- Jaime, who has succeeded in taking Riverrun bloodlessly from Brynden Tully (only for the Blackfish to escape during the handover), has refused Cersei's desperate plea for help.

- Ser Lancel has left Darry to join the newly constituted militant religious order.

- Loras Tyrell is on the verge of death after leading a successful assault on Dragonstone, previously held by Stannis.

- Sandor Clegane really is dead of his wounds, it seems (though I'm not entirely convinced of this, either).

- Petyr Baelish continues to manoeuver from the Eyrie, where Sansa stays under the name 'Alayne', posing as his natural daughter and young Richard Arryn also remains.

- Arya, in training in a Braavosi temple, has just been blinded by a man of the temple after committing murder.

- Brienne, still seeking Sansa, has fallen into the hands of a group of outlaws - splinters from Beric Dondarrion's raiders (there are hints that Beric himself may finally be dead, but maybe not) - led by Catelyn, who is horribly disfigured but alive, and made to choose between killing Jaime and hanging herself.

- Samwell has made his way to Oldtown, where he has told his tale to an archmaester, Marwyn, who has then set off to counsel Dany.

- Euron Crow's Eye has succeeded to the title of King of the Iron Islands and is raiding in force up the Mander; Victarion remains loyal to him, but Aeron and Asha have both fled.

- And the old Prince of Dorne, Doran Martell, seems to be playing a deeper game than even his own family had suspected; Princess Myrcella Baratheon, his ward, has been seriously wounded.

I'm not even going to try to set out who currently holds which castle or title, or who's where, or what's happening with all of the minor characters who seem likely to still have large roles to play in what's to come - the Freys, the Corbrays, the Kettleblacks, Mace Tyrell, Lord Nestor, Yohn Royce, Lady Merryweather, Edmure Tully, Kevan Lannister, Walder Rivers, Randyll Tarly, Aurane Waters, Bronn, Qyburn, Pycelle, Gendry...this series is massive. But one of its great virtues is Martin's ability to characterise all these figures, and keep them turning over so that now one rises to prominence, now another - and while we may guess, we never know quite what's coming.

Saturday, December 24, 2005

Bic Runga - Birds

Liking this a lot. I still think that Drive is basically perfect on its own terms (terms which include my having internalised it over the years); and, while I haven't taken it as much to heart, I reckon the more varnished Beautiful Collision is also really rather good; but Birds is somehow different from both again, and possibly her best yet. She's retained the delicacy, prettiness and ache of her earlier records, but there's more going on with this latest album, making for a richer and in some ways sweeter concoction.

For one, there's a more soulful edge to this music, in a slow burning Dusty Springfield kind of way ("Say After Me" and "If I Had You" are good examples), not just in the singing, but in the writing and arrangements, too. I'm also reminded of Carole King in places; Birds is wreathed in a backwards-looking, late 60s-through-to-70s singer-songwriter garb, though done with a modern touch. None of Runga's facility with mood and melody has been lost, but now there's also sometimes a swagger to the songwriting which is striking when compared to the (deliberate) heart-in-mouth tentativities of Drive and, to a lesser extent, Beautiful Collision (compare the way it opens, with the bright piano introduction that rings in "Winning Affair", to "Drive" or "When I See You Smile") - my favourite, though, is "Blue Blue Heart", a quirky, atypical, old fashioned-sounding piano number near the end.

For one, there's a more soulful edge to this music, in a slow burning Dusty Springfield kind of way ("Say After Me" and "If I Had You" are good examples), not just in the singing, but in the writing and arrangements, too. I'm also reminded of Carole King in places; Birds is wreathed in a backwards-looking, late 60s-through-to-70s singer-songwriter garb, though done with a modern touch. None of Runga's facility with mood and melody has been lost, but now there's also sometimes a swagger to the songwriting which is striking when compared to the (deliberate) heart-in-mouth tentativities of Drive and, to a lesser extent, Beautiful Collision (compare the way it opens, with the bright piano introduction that rings in "Winning Affair", to "Drive" or "When I See You Smile") - my favourite, though, is "Blue Blue Heart", a quirky, atypical, old fashioned-sounding piano number near the end.

Saint Etienne - Good Humor

About which I only have this to say: hurray for Saint Etienne! The songs aren't always particularly memorable, but that doesn't really matter, for how can you not like music so sparkly, so melodic, so carelessly elegant, so daintily, lightly tripping? (And "The Bad Photographer" - uptown, unabashedly 60s-styled pop!, and my introduction to the outfit on the radio, years ago - is still just brill.)

Sara Storer - Beautiful Circle

Modern country with a few nice flourishes, and Storer has a sweet voice - all up, I like it fine but it isn't lighting any fires for me.

Low - Trust

I might've got really into this a few years back (say when it first came out, in 2002), but nowadays I don't find this kind of music - hushed, drifty, minimal post-rock - particularly interesting. Oh, it's pleasant enough, but kinda boring for all that.

Janet Evanovich - Two for the Dough

More quality stuff from Evanovich - v. funny. Was searching for the right word, then found it in one of the critic's comments - 'screwball'. Laconic about it, though. Most of the cast from One for the Money returns, a few new, generally slimy figures are introduced, and it takes place largely in and around a funeral parlour. I like Stephanie Plum heaps (Names Are Important - never yet come across a Stephanie who I didn't like, in real life at least - though obviously that's only a small part of the story here). Was thinking about who should play her in a film adaptation; came up with Rachel Weisz and Miranda Otto, but both are probably way too willowy, not to mention refined-looking. Hm.

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

Song of the moment: Röyksopp - "What Else Is There?"

Oh, and I am so completely loving the newish Röyksopp single, "What Else Is There?". It's dark, luscious, epic electro-pop, garnished with interestingly fraught vocals; spends the whole time building and never quite resolves, and just demands to be listened to over and over. Reminds me of "#1 Crush", which is, even after all these years, high, high praise coming from me.

(It's here.)

(It's here.)

Gregory Maguire - Son of a Witch

One good thing about being only semi-wired into book-related news is that sometimes a new work by a favourite author comes as a complete surprise when it first appears on the shelves, and so it went with Son of a Witch, which has the double virtue of being not only a new Gregory Maguire, but also a sequel to my favourite of his previous novels, Wicked (a magnificent reimagining of The Wizard of Oz from the point of view of the so-called Wicked Witch of the West). Elphaba, as said Wicked Witch, met her end in that previous book, as we always knew she must, but her presence haunts Son of a Witch, and not only in the 'Elphaba lives' graffiti which appears on the walls and buildings of the Emerald City.

The central character is Liir, a minor but not insignificant figure in Wicked, who may or may not be Elphaba's son. The story follows his attempts to come to terms with the mysteries of his self and past, always at least potentially defined in terms of Elphaba, but in many ways its other absent centre is the appropriately named Nor, whom Liir seeks because she seems to represent a tangible link to his past (and, implicitly, to the traumatic circumstances of his separation from Elphaba in Wicked, and that latter's death). Ranging across the whole of Oz, Son of a Witch achieves the same compelling mosaic effect as did Wicked in its reimagining of Baum's magical land, although I didn't feel it to be perfect in the way that the first book is.

Liir is a strange sort of character; for much of the novel, he comes across as a cipher, his motivations and desires unclear. I'm inclined to give Maguire the benefit of the doubt and believe that the author intended this, for Liir is presented as himself being almost definitionally unsure about who he is and what he wants, but the effect is nonetheless to distance the reader from the novel's central protagonist, resulting in less emotional investment than might otherwise have been the case, and it wasn't until more than halfway through (from the sections when Liir and Candle first repair to the Apple Press Farm) that I felt that I'd been really grabbed by the story and characters. This feeling of distance from the characters is augmented by the way in which figures, many familiar from Wicked - Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Lady Glinda, Yackle, and others - seem to drift in and out of Liir's story (I found myself wondering how well this novel would have stood alone, had I not read Wicked - and read it several times, at that), often not being particularly deeply or obviously characterised.

Also adding to this feeling are the - at places quite extended - discursive excursions which Maguire dares, usually if not always grounded in Liir's thoughts. One example which sticks in my mind is the passage in which Liir wonders about the relationship between Candle's music and his own memories of the past, throwing at least half of the narrative to that point into question; another is a very nice treatment of memory and recollection which touches upon an issue dear to my own heart:

In a strange way, these kinds of passages also add to the self-reification of Maguire's novel as a retold (retooled) fairy tale - a fable - with their sense of imparting a distilled wisdom of sorts, though a wisdom expressible only in questions and revealed uncertainties, and never in final answers or simple moralising. At heart, of course, it's a fantasy - but it's a thoughtful, critical, and also very political and moral fantasy (nb distinction between 'moral' and 'moralising'). It didn't touch me as much as did Wicked, and I think that it's much in the shadow of that earlier book (even more so than was necessarily implied by its nature as a sequel), but Son of a Witch is still really rather good.

The central character is Liir, a minor but not insignificant figure in Wicked, who may or may not be Elphaba's son. The story follows his attempts to come to terms with the mysteries of his self and past, always at least potentially defined in terms of Elphaba, but in many ways its other absent centre is the appropriately named Nor, whom Liir seeks because she seems to represent a tangible link to his past (and, implicitly, to the traumatic circumstances of his separation from Elphaba in Wicked, and that latter's death). Ranging across the whole of Oz, Son of a Witch achieves the same compelling mosaic effect as did Wicked in its reimagining of Baum's magical land, although I didn't feel it to be perfect in the way that the first book is.

Liir is a strange sort of character; for much of the novel, he comes across as a cipher, his motivations and desires unclear. I'm inclined to give Maguire the benefit of the doubt and believe that the author intended this, for Liir is presented as himself being almost definitionally unsure about who he is and what he wants, but the effect is nonetheless to distance the reader from the novel's central protagonist, resulting in less emotional investment than might otherwise have been the case, and it wasn't until more than halfway through (from the sections when Liir and Candle first repair to the Apple Press Farm) that I felt that I'd been really grabbed by the story and characters. This feeling of distance from the characters is augmented by the way in which figures, many familiar from Wicked - Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Lady Glinda, Yackle, and others - seem to drift in and out of Liir's story (I found myself wondering how well this novel would have stood alone, had I not read Wicked - and read it several times, at that), often not being particularly deeply or obviously characterised.

Also adding to this feeling are the - at places quite extended - discursive excursions which Maguire dares, usually if not always grounded in Liir's thoughts. One example which sticks in my mind is the passage in which Liir wonders about the relationship between Candle's music and his own memories of the past, throwing at least half of the narrative to that point into question; another is a very nice treatment of memory and recollection which touches upon an issue dear to my own heart:

His other talent, though, was a distillation of memory into something rich and urgent. He guessed, in the hours or years remaining to him, he would remember the effect of Trism clearly, without corruption, as a secret pulse held in a pocket somewhere behind the heart.

The exact look of Trism, though, the scent and heft of him, the feel of him, would probably decay into imprecision, a shadowy form, unseen but imagined. Hardly distinguishable from an extra chimney in a valley formed by pantiled roofs of a mauntery.

In a strange way, these kinds of passages also add to the self-reification of Maguire's novel as a retold (retooled) fairy tale - a fable - with their sense of imparting a distilled wisdom of sorts, though a wisdom expressible only in questions and revealed uncertainties, and never in final answers or simple moralising. At heart, of course, it's a fantasy - but it's a thoughtful, critical, and also very political and moral fantasy (nb distinction between 'moral' and 'moralising'). It didn't touch me as much as did Wicked, and I think that it's much in the shadow of that earlier book (even more so than was necessarily implied by its nature as a sequel), but Son of a Witch is still really rather good.

Music from Baz Luhrmann's film Moulin Rouge

If there's any single film in relation to which the giving of a full context for my response to its soundtrack would involve a more dramatic violation of the 'no dwelling on the personal, no sturm und drang' rule which has (mostly) applied to these extemporanea entries than Moulin Rouge, I can't think of it.

I've just spent about ten minutes trying to work out how to express the reasons for this in a way which is neither hopelessly vague nor dreadfully revealing, without much luck. In part, it goes something like this:

1. The film is a huge retrospective landmark for me because of X

2. The music is central to the film, also because of X (or its equivalent in the film)

(If this were a proper argument, it would have a conclusion, but it makes sense to me even without one.)

(Also, there's "El Tango De Roxanne" and its own, separate story.)

So I already knew most of these songs more or less inside out from watching the film or by other means, and it's all very sweeping and swoony (and sometimes sassy), and oh so dramatic and oh so memorable (massive roll call of big names in the world of pop, too)...genius songs, great delivery...oh yeah, and it's all about love, of course.

I've just spent about ten minutes trying to work out how to express the reasons for this in a way which is neither hopelessly vague nor dreadfully revealing, without much luck. In part, it goes something like this:

1. The film is a huge retrospective landmark for me because of X

2. The music is central to the film, also because of X (or its equivalent in the film)

(If this were a proper argument, it would have a conclusion, but it makes sense to me even without one.)

(Also, there's "El Tango De Roxanne" and its own, separate story.)

So I already knew most of these songs more or less inside out from watching the film or by other means, and it's all very sweeping and swoony (and sometimes sassy), and oh so dramatic and oh so memorable (massive roll call of big names in the world of pop, too)...genius songs, great delivery...oh yeah, and it's all about love, of course.

Bernard Lagan - Loner: Inside A Labor Tragedy

Although the subject matter of this book - an account of Mark Latham's 2004 election campaign and its immediate aftermath - is intrinsically interesting, the book itself is only moderately so. It's basically a blow-by-blow account of the campaign itself (with a bit of biographical/contextual material at the beginning, and a couple of chapters dealing with the aftermath of the worse-than-expected loss at the end), and light on analysis - with its focus on recounting events rather than shedding any real light on the personalities or motivations of its key figures, it reads more as a piece of extended journalism than as a substantial work on Latham, the 2004 election, the ALP, or the Australian political scene generally.

Lagan's key theme (such as it is) is, as suggested by the book's title, that of Latham as a lone rider, prone to acting on his own instincts to the exclusion of the advice of others, and this is sketched out by reference to specific incidents as well as being grounded in his upbringing and family background. The problem for me was that, reading this book, I felt as if I was simply being reading another iteration of the received wisdom about Latham and his spectacular downfall, rather than gaining anything new or dissentient from Loner; as an only moderately attentive follower of national politics, I hoped to learn a lot more from the book than I actually did.

Lagan's key theme (such as it is) is, as suggested by the book's title, that of Latham as a lone rider, prone to acting on his own instincts to the exclusion of the advice of others, and this is sketched out by reference to specific incidents as well as being grounded in his upbringing and family background. The problem for me was that, reading this book, I felt as if I was simply being reading another iteration of the received wisdom about Latham and his spectacular downfall, rather than gaining anything new or dissentient from Loner; as an only moderately attentive follower of national politics, I hoped to learn a lot more from the book than I actually did.

Madagascar

What to say? It's consistently at least amusing and sometimes outright funny, and it's cute in the right way, and it's energetic without being annoying with it, and it has a nice message which it gets across obviously but without descending into mawkishness or preaching. Also, the penguins are the best bit.

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons - Watchmen

Yee Fui has recommended this to me on something like three separate occasions in the last six months or so, else I probably wouldn't have read it (I mean, what is this - another graphic novel?). The basic premise is that costumed vigilantes, fighting crime and assorted evils, had risen to prominence in the 1930s and 40s - 'superheroes', though largely without genuinely super-human powers - before being banned by legislation in the 70s; the narrative of Watchmen picks up in the 80s, when it begins to appear that someone is picking off these superannuated superheroes one by one, bringing at least some of them out of retirement and casting light on what others have been up to in the meantime. Also, the US won the Vietnam War and Nixon is still president. (As the series proceeds, the back story is filled in bit by bit.)

Anyway, I enjoyed reading these comics, and found the story quite thought-provoking in places. Overall, it's well crafted, and cleverly so - the way in which Moore often entwines two narrative strands in a single series of panels, so that dialogue/text ostensibly pertaining to one of the strands in fact advances the other at the same time, is particularly pleasing from a literary/neatness point of view. My main quibble is that the pacing seemed a bit weird - perhaps I've just been spoilt by the Sandman series, where everything seems to come together in exactly the right way, both within individual volumes and in the context of the series as a whole, but Watchmen somehow seemed a bit off-pace...I can't put it any better than that. I also felt that there wasn't a single overriding 'point' to the series, or at least not one that emerges particularly clearly; its ideas and politics seem a bit muddled, but perhaps the point is more to provoke thought (particularly about moral systems and responsibility) while entertaining than to push any particular barrow...

Anyway, I enjoyed reading these comics, and found the story quite thought-provoking in places. Overall, it's well crafted, and cleverly so - the way in which Moore often entwines two narrative strands in a single series of panels, so that dialogue/text ostensibly pertaining to one of the strands in fact advances the other at the same time, is particularly pleasing from a literary/neatness point of view. My main quibble is that the pacing seemed a bit weird - perhaps I've just been spoilt by the Sandman series, where everything seems to come together in exactly the right way, both within individual volumes and in the context of the series as a whole, but Watchmen somehow seemed a bit off-pace...I can't put it any better than that. I also felt that there wasn't a single overriding 'point' to the series, or at least not one that emerges particularly clearly; its ideas and politics seem a bit muddled, but perhaps the point is more to provoke thought (particularly about moral systems and responsibility) while entertaining than to push any particular barrow...

Thursday, December 15, 2005

The Virgin Suicides

I remember, when I watched this at the cinema, I thought that it was one of the saddest and truest things that I'd ever seen. (Hard to believe that it's been five years already.) Then, as now, I was well nigh overcome by the sharp sweet nostalgia which fills the film's every scene, a nostalgia that works on two levels: for a sort of hazy, collectively dreamt image of suburban America in the 70s, available even to those like myself who never lived through those years, AM radio, sunshine and shifting shadows, innocence and glitter, transience and loss; and for those awkward, inchoate, grace-touched teenage years which always, in retrospect, appear bathed in a strange transformative glow, light and heavy all at once, seemingly limitless potential mingled with a queer, lump-in-throat, ungraspable sense of what was always already passing.

I'm listening to the soundtrack now, wrapping myself for a little longer in the dreamy cocoon of The Virgin Suicides, and finding that I don't want to say much more. The film has retained its gentle glamour and its mystery, and I adored it all over again. It's like it never went away.

I'm listening to the soundtrack now, wrapping myself for a little longer in the dreamy cocoon of The Virgin Suicides, and finding that I don't want to say much more. The film has retained its gentle glamour and its mystery, and I adored it all over again. It's like it never went away.

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

Charlotte Greig - Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow? Girl Groups From The 50s On

Workmanlike and readable account of girl groups in pop, defined by Greig as 'group[s] of three or more young women singing pop tunes in vocal harmony together, using a style which originated in fifties' teenage American rock 'n' roll', done with a strong feminist slant which is mostly (though not always) convincing. Starts off in the 50s, skipping through the Chantels, the Shirelles, the Crystals and others through to the Ronettes (apparently they were seen, at least at one point, as the female Rolling Stones!) and of course my favourites the Shangri-Las, then on to Diana Ross and the Supremes and the whole Motown scene. I got pretty bogged down in the post-Motown chapters, dealing with girl groups in the 70s and 80s - it's not as much fun reading about outfits that I've never even heard of, never mind heard - and the book ends with the interesting but somewhat forced claim that female hip hop crews like Salt 'n Pepa are the contemporary torch bearers of the girl group ethos (it was published in '89, before the big pop revival of the 90s).

It's a fun read, engagingly written and full of photos, and Greig does a good job of integrating her study with the broader musical streams of the times, though of course with particular emphasis on those who directly influenced and affected the girl group scene - Carole King, Ellie Greenwich, Dusty Springfield, Motown impresario Berry Gordy, and songwriters Holland-Dozier-Holland and later Stock, Aitken and Waterman are some of those who are prominent, with acts like the Beatles, Michael Jackson and Madonna having walk-on parts. It's also well contextualised with the social context and changing social attitudes within which the music has been produced, particularly in terms of race, gender and sexuality, though sometimes Greig's claims seem rather too large; for example, she asserts that, by the 60s, '[t]he girl-group ethos had successfully penetrated the male world of popular music to such a degree that men as well as women could now sing innocent, idealistic songs of love and romance', which at best seems something of an overstatement, and is more likely a complete inversion of cause and effect.

One of the best things about the book is its focus on interviews with artists and industry types, providing some interesting insights into the way the music industry has worked in the past (and probably largely continues to operate), particularly as regards the degree to which artists have traditionally been completely exploited by, well, basically everyone - managers, producers, record companies...also interesting to read about the Brill Building method of production in the early days, when artists were signed and records laid down and released in a matter of days, and songwriters worked in adjacent rooms with just a piano and a fistful of ideas.

It's a fun read, engagingly written and full of photos, and Greig does a good job of integrating her study with the broader musical streams of the times, though of course with particular emphasis on those who directly influenced and affected the girl group scene - Carole King, Ellie Greenwich, Dusty Springfield, Motown impresario Berry Gordy, and songwriters Holland-Dozier-Holland and later Stock, Aitken and Waterman are some of those who are prominent, with acts like the Beatles, Michael Jackson and Madonna having walk-on parts. It's also well contextualised with the social context and changing social attitudes within which the music has been produced, particularly in terms of race, gender and sexuality, though sometimes Greig's claims seem rather too large; for example, she asserts that, by the 60s, '[t]he girl-group ethos had successfully penetrated the male world of popular music to such a degree that men as well as women could now sing innocent, idealistic songs of love and romance', which at best seems something of an overstatement, and is more likely a complete inversion of cause and effect.

One of the best things about the book is its focus on interviews with artists and industry types, providing some interesting insights into the way the music industry has worked in the past (and probably largely continues to operate), particularly as regards the degree to which artists have traditionally been completely exploited by, well, basically everyone - managers, producers, record companies...also interesting to read about the Brill Building method of production in the early days, when artists were signed and records laid down and released in a matter of days, and songwriters worked in adjacent rooms with just a piano and a fistful of ideas.

Neko Case & Her Boyfriends - The Virginian

Back to the beginning for my favourite alt-country/indie-pop rockabilly cum torch chanteuse. I think that The Virginian was her solo debut, and it sees her really belting the songs out (she's a much more subtle, though no less powerful, singer these days, circa Blacklisted) - it's brassy and comes across as fairly unpolished, with her vocals riding high above the rest of the music and often, on cuts like "Karoline" and "Honky Tonk Hiccups", giving herself over to all kinds of idiosyncratic phrasings, growls and whoops. Some of the hooks, too, are a wee bit outrageous (and this from a boy who still numbers "Wuthering Heights" amongst his favourite songs!) - "Bowling Green" comes to mind, as does "Thanks A Lot" - but the exuberance and the strength of her singing make it work.

In general, too, the record's quite a bit more 'down home' and sorta old-time country, and more covers-oriented, than Case's more recent work. It also tends towards the upbeat end of her range, though there are some signs of the balladry that she'd later carry off with such aplomb, particularly on songs like the rather wonderful second half double punch of the title cut and "Duchess".

So I'm not quite sure what I think of The Virginian - a part of me thinks that it's ace, while another part just can't stop dwelling on the certainty that it can't hold a candle to Blacklisted...presumably the answer is that both are true.

In general, too, the record's quite a bit more 'down home' and sorta old-time country, and more covers-oriented, than Case's more recent work. It also tends towards the upbeat end of her range, though there are some signs of the balladry that she'd later carry off with such aplomb, particularly on songs like the rather wonderful second half double punch of the title cut and "Duchess".

So I'm not quite sure what I think of The Virginian - a part of me thinks that it's ace, while another part just can't stop dwelling on the certainty that it can't hold a candle to Blacklisted...presumably the answer is that both are true.

A couple of rewatches: Chungking Express and The Nightmare Before Christmas

Michelle and David came over last night, and we watched a couple of the things that I have lying around my room - Chungking Express and The Nightmare Before Christmas. I saw the latter of those recently enough that I don't have much to add to my initial impressions; as to Chungking Express (thoughts after first viewing here), well, I suppose that my attitude towards it was a bit more critical this time round, meaning that I picked up on more of the little parallels between the two stories and the ways that they actually intersect, and also was more aware of how much each storyline needs the other in order to work, but it's still just as good...I should get myself a dvd copy of this one - like Amelie, it'd be a good one to be able to watch over and over, for comfort's sake...

Monday, December 12, 2005

The Quick and the Dead

Westerns are generally fun, and I enjoy films where characters get picked off one by one (even when, as is usually the case, it's pretty plain who's going to be left standing, and in what order the others will fall), which possibly goes some way to explaining my soft spot for The Quick and the Dead (this ain't the first time I've seen the film) and how I came to be watching it on tv tonight, despite the bane of commercial breaks. There's not much to it, but Sharon Stone carries off the lead role well, and Hackman, Crowe and DiCaprio (not a half bad cast, come to think of it) all get the job done in style. Alas, the scene where Ellen and Cort get it on was excised - I don't recall it as being particularly exciting, but for some reason, it's one of my strongest impressions of the film (probably because most of the rest of the running time is taken up by one gunfight after another). Also, the holes that get blown in people from time to time were a bit weird/distracting. Oh yeah, and there's no real building of tension or any proper pacing. Pfooie - it was still fun.

Sunday, December 11, 2005

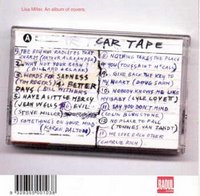

Lisa Miller - Car Tape

There's a nice anecdote in the liner notes to one of Lisa Miller's earlier albums, Quiet Girl With A Credit Card (I think it was her debut, actually), concerning some people hearing Miller sing and taking the songs for standards, only to learn that she had written them herself. Actually, two of the best songs on that album are covers - her takes on "[A] Woman Left Lonely" and Bob Dylan's "You're A Big Girl Now" are both spectacularly good - and so it seemed likely that Car Tape, an album made up entirely of cover versions, would be a good one.

And so it is, although in at least one way it might as well be made up entirely of Miller's own compositions, given that none of these songs are at all famous (indeed, I've only even heard of a handful of the original artists). I really think that she's a genuine talent, as a songwriter (though obviously that's not on show on this particular record), as an interpreter of others' songs, and as a singer - in those last two dimensions, in particular, I don't reckon that she has too many peers.